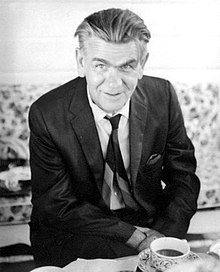

Paul Mattick

Paul Mattick | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | March 13, 1904 |

| Died | February 7, 1981 (aged 76) |

| Occupation(s) | Council Communist theoretician and social revolutionary, Toolmaker |

| Years active | 1918– 1980 |

| Known for | Left communist anti-Bolshevism, developing Karl Marx's and Henryk Grossman's theory of capitalism for contemporary economics |

| Partner(s) | Frieda Mattick, Ilse Hamm Mattick |

Paul Mattick Sr. (March 13, 1904 – February 7, 1981) was a German-American Marxist political writer, political philosopher and social revolutionary, whose thought can be placed within the council communist[1] and left communist traditions.

Throughout his life, Mattick continually criticised Bolshevism, Vladimir Lenin and Leninist organisational methods, describing their political legacy as "serving as a mere ideology to justify the rise of modified capitalist (state-capitalist) systems, which were [...] controlled by way of an authoritarian state".[2]

Early life

[edit]Born in Słupsk, Pomerania in 1904 and raised in Berlin by class-conscious parents, Mattick was already at the age of 14 a member of the Spartacists' Freie Sozialistische Jugend. In 1918, he started to study as a toolmaker at Siemens AG, where he was also elected as the apprentices' delegate on the workers' council of the company during the German Revolution.

Implicated in many actions during the revolution, arrested several times and threatened with death, Mattick radicalized along the left and oppositional trend of the German communists. After the "Heidelberg" split of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD; a successor to the Spartacist League) and the formation for the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD) in the spring of 1920, he entered the KAPD and worked in the youth organization Rote Jugend, writing for its journal. In March 1920 he participated in street fighting against the rightist Kapp Putsch, in which his lifelong friend Reinhold Klingenberg was shot and lost a leg.[3]

In 1921, at the age of 17, Mattick moved to Cologne to find work with Klockner for a while, until strikes, insurrections and a new arrest destroyed every prospect of employment. He was active as an organizer and agitator in the KAPD and the AAU in the Cologne region, where he got to know Jan Appel among others. He also established contacts with intellectuals, writers and artists working in the AAUE founded by Otto Rühle. These included the Cologne Progressives, a group formed around Franz Seiwert.[3]

With the continuing decline of radical mass struggle and revolutionary hopes, especially after 1923, and having been unemployed for a number of years, Mattick emigrated to the United States in 1926, whilst still maintaining contacts with the KAPD and the AAUE in Germany.

In the United States

[edit]In the United States, Mattick carried through a more systematic theoretical study, above all of Karl Marx. In addition, the publication of Henryk Grossman's principal work, Das Akkumulations - und Zusammenbruchsgesetz des Kapitalistischen Systems (1929), played a fundamental role for Mattick, as Grossman brought Marx's theory of accumulation, which had been completely forgotten, back to the centre of debate in the workers' movement.

| Part of a series on |

| Left communism |

|---|

|

To Mattick, Marx's "critique of political economy" became not a purely theoretical matter but rather directly connected to his own revolutionary practice. From this time, Mattick focused on Marx's theory of capitalist development and its inner logic of contradictions inevitably growing to crisis as the foundation of all political thoughts within the workers' movement.

Towards the end of the 1920s, Mattick had moved to Chicago, where he first tried to unite the different German workers' organisations. Taking night classes to improve his English, Mattick fell into the orbit of the Proletarian Party, a cliquish grouping of independent Marxists which had been successively drummed out of the Socialist Party (in 1919) and the Communist Party (in 1920), now going it alone with their own party organization. Mattick participated in their meetings and contributed to their party publications for several years, during which he also sometimes spoke in the nighttime lecture series at the bohemian Dil Pickle Club, an IWW hangout.[4] In 1931, under the sponsorship of a local federation of German-speaking socialist clubs and sports groups, he took over as editor of the defunct German-language Chicagoer Arbeiter-Zeitung, a newspaper steeped in radical tradition and at one time edited by August Spies and Joseph Dietzgen. Mattick put out 10 monthly issues between February and December 1931, writing much of the paper's content himself, but the paper failed to achieve a large enough readership to be self-sustaining, and folded at the end of the year.[5] For a period, he joined the Industrial Workers of the World (known as the IWW or Wobblies), who were the only revolutionary union organization existing in America that, in spite of national or sectoral differences, assembled all workers in One Big Union, so as to prepare the general strike to bring down capitalism. However, the golden age of the Wobblies' militant strikes had already passed by the beginning of the thirties, and only the emerging unemployed movement again gave the IWW a brief regional development. In 1933, Paul Mattick drafted a programme for the IWW trying to give the Wobblies a more solid 'Marxist' foundation based on Grossman's theory, although it did not improve the organization's condition. In 1934, Mattick, some friends from the IWW as well as some expellees from the Leninist Proletarian Party formed the United Workers Party, later to be renamed Group of Council Communists. The group kept close contacts with the remaining small groups of the German/Dutch Left communism in Europe and published the journal International Council Correspondence, which through the 1930s became an Anglo-American parallel to the Rätekorrespondenz of the Dutch GIC(H). Articles and debates from Europe were translated along with economic analysis and critical political comments of current issues in the United States and elsewhere in the world.

Apart from his own factory work, Mattick organized not only most of the review's technical work but was also the author of the greater part of the contributions which appeared in it. Among the few willing to offer regular contributions was Karl Korsch, with whom Mattick had come into contact in 1935 and who remained a personal friend for many years from the time of his emigration to the United States at the end of 1936.

As European council communism went underground and formally "disappeared" in the second half of the 1930s, Mattick changed Correspondence's name from 1938 to Living Marxism and from 1942 to New Essays.

Like Karl Korsch and Henryk Grossman, Mattick had some contact with Max Horkheimer's Institut fur Sozialforschung (the later Frankfurt School). In 1936, Mattick wrote a major sociological study on the American unemployed movement for the Institute, although it remained in the Institute's files, to be published only in 1969 by the SDS publishing house Neue Kritik.

World War II and after

[edit]After the United States' entry into World War II and the post-war Mccarthyism, the left in America experienced repression. Mattick retired at the beginning of the 1950s to the countryside, as part of the rustic "back to the land" colony clustered around Scott Nearing near Winhall, Vermont, where he managed to survive through occasional jobs and his activity as a writer. In the postwar development Mattick took part in only small and occasional political activities, writing small articles for various periodicals from time to time. From the forties and up through the fifties, Mattick went through a study of John Maynard Keynes and compiled a series of critical notes and articles against Keynesian theory and practice. In this work, he developed Marx's and Grossman's theory of capitalist development further to meet the new phenomena and appearances of the modern capitalism critically.

With the general changes of the political scene and the re-emergence of more radical thoughts in the sixties, Paul Mattick made some more elaborated and important political contributions. One main work was Marx and Keynes: The Limits of Mixed Economy from 1969, which was translated into several languages and had quite an influence in the post-1968 student movement. Another important work was Critique of Herbert Marcuse: The one-dimensional man in class society, in which Mattick forcefully rejected Marcuse's thesis that the proletariat, as Marx understood it, had become a mythological concept in advanced capitalist society. Although he agreed with Marcuse's critical analysis of the ruling ideology, Mattick demonstrated that the theory of one dimensionality itself existed only as ideology. Marcuse subsequently affirmed that Mattick's was the best critique to which his book was subjected.[6]

Later life

[edit]Up through the seventies, many old and new articles by Mattick were published in different languages for various publications. In the academic year 1974-75, Mattick was engaged as visiting professor at the "Red" Roskilde University in Denmark. Here, he held lectures on Marx' critique of political economy, on the history of the workers movement and served as critical co-referent at seminars with other guests such as Maximilien Rubel, Ernest Mandel, Joan Robinson and others. In 1977, he completed his last important lecture tour of the University of Mexico City. He spoke in West Germany only twice: in 1971 at Berlin and in 1975 at Hanover.

In his last years, Mattick thus succeeded in getting a small audience within the new generations for his views. In 1978, a major collection of articles from over forty years appeared as Anti-Bolshevik Communism. Mattick died in February 1981 leaving an almost finished manuscript for another book, which was later edited and published by his son, Paul Mattick, Jr., as Marxism - Last Refuge of the Bourgeoisie?.[citation needed]

Bibliography

[edit]- The Masses and the Vanguard

- Council Communism

- Intro to Anti-Bolshevik Communism

- Capitalism and ecology: from the decline of capital to the decline of the world

- Marx and Keynes: The Limits of the Mixed Economy, Boston: Porter Sargent, 1969

- Anti-Bolshevist Communism in Germany, New York: Telos Press, 26, Winter 1975-76

- Anti-Bolshevik Communism, Wales: The Merlin Press, 1978 (reprinted 2007) ISBN 978-0-85036-223-7

- Economic Crisis and Crisis Theory, London: Merlin Press, 1981 (transl. Paul Mattick Jr.)

- Marxism: The Last Refuge of the Bourgeoisie?, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1983 (ed. Paul Mattick, Jr.); NY: Routledge, 2015.

References

[edit]- ^ Mattick, Paul. "Council Communism".

- ^ Mattick, Paul (2007) [1978]. Anti-Bolshevik Communism. Wales: The Merlin Press. pp. Introduction, XI. ISBN 978-0-85036-223-7.

- ^ a b Roth 2014, p. 27.

- ^ Roth 2014, p. 134.

- ^ Roth 2014.

- ^ Aronowitz, Stanley (2001). The Last Good Job in America: Work and Education in the New Global Technoculture. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield. pp. 258. ISBN 978-0742509757.

- Roth, Gary (2014). Marxism in A Lost Century: A Biography of Paul Mattick. Brill.

- 1904 births

- 1981 deaths

- American anti-capitalists

- German anti-capitalists

- People from Słupsk

- People from the Province of Pomerania

- Communist Workers' Party of Germany politicians

- Marxist theorists

- German emigrants to the United States

- American communists

- American Marxists

- German Marxists

- Industrial Workers of the World members

- Council communists