Charles Robert Cockerell

Charles Robert Cockerell | |

|---|---|

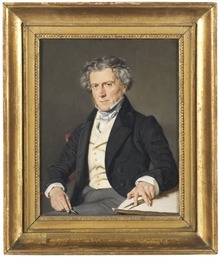

Charles Robert Cockerell (portrait by Ingres, 1817) | |

| Born | 27 April 1788 London, England |

| Died | 17 September 1863 (aged 75) 13 Chester Terrace, Regent's Park, London, England |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Spouse |

Anna Maria Rennie (m. 1828) |

| Children | 10, including Frederick |

| Parent(s) | Samuel Pepys Cockerell Anne Whetham |

| Awards | Royal Gold Medal (1848) |

| Buildings | Ashmolean Museum |

Charles Robert Cockerell RA (27 April 1788 – 17 September 1863) was an English architect, archaeologist, and writer. He studied architecture under Robert Smirke. He went on an extended Grand Tour lasting seven years, mainly spent in Greece. He was involved in major archaeological discoveries while in Greece. On returning to London, he set up a successful architectural practice. Appointed Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts, he served in that position between 1839 and 1859. He wrote many articles and books on both archaeology and architecture. In 1848, he became the first recipient of the Royal Gold Medal.

Background and education

[edit]Charles Robert Cockerell was born in London on 27 April 1788,[1] the third of eleven children of Samuel Pepys Cockerell, educated at Westminster School from 1802, where he received an education in Latin and the Classics.[2] From the age of sixteen, he trained in the architectural practice of his father, who held the post of surveyor to East India House, and several London estates.[3] From 1809 to 1810 Cockerell became an assistant to Robert Smirke,[4] helping in the rebuilding of Covent Garden Theatre (the forerunner of today's Royal Opera House).

Grand Tour

[edit]

On 14 April 1810 he set off on the Grand Tour.[5] Due to the Napoleonic Wars much of Europe was closed to the British, so he headed for Cadiz, Malta and Constantinople (Istanbul); from there he went to Troy, finally arriving in Athens, Greece by January 1811.[6] In Constantinople he met John Foster (architect) who would accompany him on his tour.[7] In April 1811 he was in Aegina where he helped excavate the Temple of Aphaea (which he called the Temple of Jupiter),[8] finding fallen fragmentary pediment sculptures (these are now in Germany), which he discovered were originally painted.[9] On 18 August 1811 he set out with three companions from Zakynthos on a tour of Morea, aiming for the temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae in Arcadia.[10] The magnificent Bassae Frieze that Cockerell discovered at the temple was eventually excavated and sold to the British Museum.[10] His tour continued visiting, Sparta, Argos, Tiryns, Mycenae, Epidaurus and Corinth returning to Athens.[11] It was there that he met Frederick North, who persuaded Cockerell and Foster to accompany him to Egypt,[12] setting off in late 1811, they travelled via Crete, where North abandoned the idea, so Cockerell and Foster decided to visit the Seven churches of Asia and visit Hellenistic sites along the way,[12] the itinerary was: Smyrna, Pergamon, Sardis, Ephesus, Priene and Side.[12] They arrived in Malta on 18 July 1812, where Cockerell was confined to bed for three weeks with a fever. By 28 August 1812 they were in Sicily, where they stayed several months studying the chief Greek temples, drawing a reconstruction of the Temple of the Olympian Zeus, Agrigento.[12] From December 1813 to February 1814 he was in Syracuse, Sicily working on drawings for a projected book on Aegina, Phigalia and the Bassae Frieze, he left to return to Athens where he continued work on the book, only to fall ill again on 22 August, he was still ill on 10 November, when he wrote to his sister.[12] On his recovery he continued his travels, in January 1814 he was in Ioannina, where he had an audience with Ali Pasha.[13] Returning to Athens, before going on in May 1814 to Zakynthos to attend the sale of the Bassae Frieze. Back in Athens he met an old school friend John Spencer Stanhope and his brother, between August and October he was struck down by the fever again, but was well enough to attend a celebration of the anniversary of the Battle of Salamis at Piraeus on 25 October.[13] In December 1814 he returned to the Temple of Aphaea for a fortnight to check and correct his drawings.[14] In a letter of 23 December 1814 he details his re-discovery of entasis, he enclosed a sketch for Robert Smirke of one of the Parthenon columns showing its outline.[15]

Thanks to the abdication of Napoleon in April 1814, the Kingdom of Sicily and Rome were now open to the British, so on 15 January 1815 Cockerell left for Naples in the company of Jakob Linckh, they visited Pompeii and only reached Rome on 28 July.[15] The circle he mixed with in Rome included: Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Antonio Canova, Bertel Thorvaldsen, Peter von Cornelius, Friedrich Wilhelm Schadow, Heinrich Maria von Hess, Ludwig Vogel, Johannes Riepenhausen, Franz Riepenhausen and the Knoering brothers.[9] Writing to his father in August 1815 he said 'I should be out of my wits at the attention paid me here, I have an audience daily of savants, artists & amateurs who come and see my drawings; envoys and ambassadors beg to know when it will be convenient for me to show them some sketches; Prince Poniatowski and Prince Saxe-Gotha beg to be permitted to see them...'.[9] Much of his time in Rome was spent on preparing his drawings for publication.[16] Writing to his father on 28 December saying he had purchased copies of Domenico Fontana's Della transportatione dell'obelisco Vaticano e delle fabriche di Sisto V and Martino Ferraboschi's Architettura della basilica di S. Pietro in Vaticano.[17] In 1816 Cockrell moved on to Florence.[18] Cockerell was presented to Ferdinand III, Grand Duke of Tuscany and was awarded the diploma of Academician of the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno.[19] While in Florence in early 1816 Cockerell produced a design for Wellington Palace for Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, it would have been in the style of Greek Revival architecture on a scale to rival Blenheim Palace, though in the end nothing came of the proposal.[20] In June he suffered another bout of ill health. From Florence Cockerell continued his tour visiting Pisa for a month,[21] returning to Florence, he set out on 13 September for Bologna, Ferrara, then travelling by boat along the Po to Venice where he stayed three weeks.[22] From Venice, Cockerell visited Andrea Palladio's buildings along the Brenta (river) and at Vicenza,[23] passing on to Mantua and the Palazzo del Te, Parma, Milan, Genoa and back to Rome from where he set off in March 1817 to return home via Paris.[24]

Return to England

[edit]Cockerell returned to London on 17 June 1817, over seven years since his departure, originally the plan had been for a three-year Grand Tour.[25] Cockerell set about preparing his drawings of Greek antiquities for exhibition at the Royal Academy.[25] Cockerell was living and working at 8 Old Burlington Street, it was owned by his father, where his office remained until 1830, he lived elsewhere on marrying in 1828.[26] From 1832 to 1836 he rented as his office 34 Savile Row (which was at the bottom of the garden of 8 Old Burlington Street).[26] Cockerell was a member of three gentlemen's clubs: Athenaeum Club, Travellers Club (he was a founder member, 5 May 1819) and Grillion's to which he was elected in 1822.[27]

In 1819 he was appointed Surveyor of the Fabric of St Paul's Cathedral,[28] where his works included the replacement, in 1821, of the ball and cross on the dome.[3]

With Jacques Ignace Hittorff and Thomas Leverton Donaldson, Cockerell was also a member of the committee formed in 1836 to determine whether the Elgin Marbles and other Greek statuary in the British Museum had originally been coloured (see Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects for 1842).

He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy on 2 November 1829,[29] and an academician on 10 February 1836,[29] his diploma work being his design for the Palace of Westminster competition.[29] In September 1839, he was appointed Professor of Architecture at the Academy, following the death of William Wilkins.[30] He won the first Royal Gold Medal for architecture in 1848[31] and became president of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1860.[31]

In 1833, following the resignation of Sir John Soane, he became surveyor to the Bank of England, and made additions to its London building, as well as designing branch offices in Manchester, Liverpool, Bristol, and Plymouth.[3]

His exhibits at the Royal Academy included reconstructions of ancient Rome and Athens and a capriccio entitled "Tribute to the Memory of Sir Christopher Wren, being a Collection of his Principal Works"; these became well known through published engravings[3]

As an archaeologist, Cockerell is remembered for removing the reliefs from the temple of Apollo at Bassae, near Phigalia, which are now in the British Museum. Replicas of these reliefs were included in the frieze of the library of the Travellers Club.

The Royal Academy of Arts composed a brief commemorative biography of Cockerell, including the following sentiment which speaks of his great work as a student of architecture:

At the heart of Cockerell's emotional experience of the power of the antique to fire the imagination lay an extraordinary visual sensitivity to the mass and volume of the components of architecture, which for him were never mere abstract, weightless forms or quotations borrowed from the past, but acted together as a constantly renewable expression of man's innate need to create beauty on earth.

Architectural career

[edit]

Cockerell had grave doubts about the wisdom of using Greek Revival architecture in nineteenth-century England, in his diary of 1821 he had this to say:

Until the attention of the world was drawn to the study of Greece by the spirit of the last century by Barthélemy's Anacharsis & thence to the study of Greek architecture by the researches of Stuart & Revett architecture had for its guide this Country the Old Italian masters & their valuable commentaries & publications of the anc[ien]t arch[itectur]e of Rome and Italy. No great enormities could arise under such guidance, but since the rage for Greek has been amongst us all the rules which formerly protected us are now set aside & we are at sea without compas ...we stick a slice of an anc[ien]t Greek Temple to a Barn which is called breadth & simplicity, than which nothing can be more absurd, as the Greek Houses were certainly of wood & brick & plaister [Sic] painted & temporary things. I am sure that the grave & solemn arch[itectur]e of Temples were never adopted to Houses, but a much lighter style, as we may judge by the vases, the object being space & commodiousness.[32]

Cockerell's first building (1818–20) was in the style of Tudor architecture, the brick building at Harrow School, now known as the 'old schools' has twin crow-stepped gables.[33] His next commission was the classical Hanover Chapel (1821–25) Regent Street, with its twin towers and projecting tetrastyle Ionic portico, later demolished (1896).

Personal life

[edit]On 23 March 1828 he proposed marriage to, and was accepted by, Anna Maria Rennie (daughter of John Rennie the Elder) while strolling in the grounds of Dalmeny House, Scotland, she was twenty-five, and he was nearly forty.[34] The engagement ring was bought for £27 10s 0d in Edinburgh on 29 March and the wedding took place on 4 June 1828 in St James's Church, Piccadilly, the Bishop of London William Howley officiating.[34] The honeymoon started at Liphook, moving on to Chichester, the Isle of Wight, crossing to Portsmouth where they toured the Dockyard, and finally on 14 June The Grange, Northington.[35] The couple set up home at 87 Eaton Square.[36] In 1838 the family moved to Ivy House, North End, Hampstead.[31]

The first of their ten children, a son, Robert Charles was born in 1829 but died five years later, followed in 1832 by the second son John Rennie, a daughter in 1832, then in 1833 a son Frederick Pepys Cockerell who became an architect, followed in 1834 by Robert who became a soldier and died aged twenty in the Battle of Alma, then two more daughters and three sons, the youngest Samuel Pepys (1844–1921) would edit and publish in 1903 his father's travel diaries.[31]

By 1851 Cockerell was in poor health and spent that summer recuperating at his sister Anne Pollen's house in Somerset,[37] from this time on his architectural practice virtually ceased. The family moved to 13 Chester Terrace, where he died on 17 September 1863, aged 75.[37] He was buried in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral,[28] a perk of being the cathedral's surveyor,[38] his marble tomb consists of his profile portrait, suspended from an Ionic column, surrounded by rich embellishment.[39]

Freemasonry

[edit]Whilst in Edinburgh and working on the National Monument with fellow Freemason, William Henry Playfair, Cockerell was Initiated into Scottish Freemasonry in Lodge Holyrood House (St Luke's), No.44 on 18 May 1824.[40]

Published works

[edit]Cockerell's published works include:[41]

- Travels in Southern Europe and the Levant, 1810–17 : the Journal of C.R. Cockerell, R.A., S.P. Cockerell Ed 1903[42]

- Progetto di collocazione delle statue antiche esistenti nella Galleria di Frienza che rappresentano la Favola di Niobe, Firenza 1816

- 'Le Statue della Favola di Niobe dell' Imp.eR. Galleria di Firenza situate nella primitiva loro disposizione da C.R. Cockerell, Firenza 1818

- On the Aegina Marbles, Journal of Science and the Arts, VI 327-31

- On the Labyrinth of Crete, in Travels in Various Countries, Robert Walpole Ed 2 vols, 1817 and 1820 vol. II Pages 402–9

- An Account of Hanover Chapel, in Regent Street, in The Public Buildings of London, J. Britton & A.C. Pugin 2 vols, 1825–28 vol. II pages 276–82

- The Temple of Jupiter Olympius at Agrigentum, supplement to Stuart & Revetts Antiquities of Athens, 1829

- The Pediment Sculptures of the Parthenon, as part VI of A Description of the Collection of Ancient Marbles in the British Museum, 1830

- Plan and Section of the New Bank of England Dividend, Pay and Warrant Offices and Accountant's Drawing Office 1835

- The Architectural Works of William of Wykeham, Proceedings of the Archaeological Institute at Winchester, 1845

- Ancient Sculptures in Lincoln Cathedral, in Proceedings of the Archaeological Institute, 1850

- Iconography of the West Front of Wells Cathedral, with an appendix on the Sculptures of other Mediaeval Churches in England, 1851

- Illustrations, Architectural and Pictorial of the Genius of M.A. Buonarroti with descriptions of the plates by C.R. Cockerell, Canina 1857

- Statement by Mr Cockerell on the Wellington Monument Competition, The Builder XV p. 427, 1857

- Address, Royal Institute of British Architects, Session, 1859–60, 111–13, 1859

- On the Painting of the Ancients, in the Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal, XXII p42-44 & 88–91, 1859

- Presidential Address, Royal Institute of British Architects, Session, 1861–62, 1860

- The Temples of Jupiter Panhellenius at Aegina and of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae, 1860

- Architectural Accessories of Monumental Sculpture, in the Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal, XXIV p333-6, 1861

- A Descriptive Account of the Sculptures of the West Front of Wells Cathedral photographed for the Architectural Photographic Association, 1862

Architectural works

[edit]1820s

[edit]- 1818–20 – Old Schools, Harrow School, in Tudor Gothic, brick with stone dressings

- 1819-36 – Oakly Park, Shropshire, remodelling work[43]

- 1820–26 – Loughcrew House, County Meath, Ireland.[44]

- 1821 – Tower and facade of St. Mary's church Banbury, in classical style, the body of the church is by his father

- 1821 – Library and Chapel, Bowood House, Wiltshire

- 1821 – Hanover Chapel, Regent Street, London (demolished)

- 1822–27 – The Saint David's Building, University of Wales, Lampeter.

- 1824–28 – Langton House, Dorset, (demolished)

- 1824–29 – The National Monument, Edinburgh, with William Henry Playfair, unfinished.

- 1827-28 - Newbridge Lodge, Wynnstay, North Wales[45]

- 1829 – Church of Holy Trinity, Hotwells, Bristol.[46]

1830s

[edit]- 1831 – Westminster, Life and British Fire Office, London, (demolished)

- 1835 – The Bank of England, Courtney Street, Plymouth.

- 1836–37 – Cambridge University Library, only the north wing of the quadrangular design was built.[47]

- 1837 – London and Westminster Bank, City of London, (demolished)

- 1838 – The Chapel, Killerton, in a Neo-Norman style

- 1838 – London & Westminster Bank, Lothbury, London (with William Tite).

- 1839–45 – The Ashmolean Museum and Taylor Institution, Oxford University.

1840s

[edit]- 1840 – Seckford Hospital, Woodbridge, Suffolk.[48]

- 1841 – Sun Fire Office, London (demolished)

- 1844–47 – The Bank of England, Bristol.[49]

- 1845 – The Bank of England, King Street, Manchester.

- 1845–48 – The Bank of England, Castle Street, Liverpool.

- 1848 – Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge University, designed the interiors after the death of the architect George Basevi.

- 1848 – Bank Chambers, Cook Street, Liverpool (demolished)

1850s

[edit]- 1851–54 – St. George's Hall, Liverpool, designed the interiors after the death of the architect Harvey Lonsdale Elmes.

- 1855-57 – Liverpool, London and Globe Building, Liverpool [50]

Gallery of architectural works

[edit]-

Entrance to the Ashmolean Museum

-

Taylor Institute, with Ashmolean Museum behind

-

Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool showing Minton tile floor

-

Internal door, Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Organ platform, Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Detail of floor, Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Organ, Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Court room, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Court room, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Chandelier, Main Hall, St. George's Hall, Liverpool

-

Bank of England, Liverpool

-

Bank of England building, Manchester

-

Holy Trinity Hotwells, Bristol

-

Old Schools, Harrow School

-

The St David's Building at the University of Wales, Lampeter

-

St. Mary's Banbury

-

Scottish National Monument, Edinburgh, with William Henry Playfair, unfinished

-

Library, Bowood House

-

Former Cambridge University Library

-

The Chapel, Killerton

References

[edit]- ^ page 3, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 4, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b c d "The Late Mr Charles Robert Cockerell, R.A.,, Architect". The Builder. 21. 1863.

- ^ page 5, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 6, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 7, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 8, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 9, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b c page 18, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 12, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 13, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b c d e page 14, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 15, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 16, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 17, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 20, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 21, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 22, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 23, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ pages 24–27, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 27, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ pags 31, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ pags 35, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ pags 36, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 38, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 39, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 42, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 222, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840, Howard Colvin, 2nd Edition 1978, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-3328-7

- ^ a b c page 58, Masterworks: Architecture at the Royal Academy of Arts, Neil Bingham, 2011 Royal Academy of Arts, ISBN 978-1-905711-83-3

- ^ page 105, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b c d page 243, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 65, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 135, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 51, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ pages 51–52, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ page 41, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ a b page 244, The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, Zwemmer Ltd, ISBN 0-302-02571-5

- ^ "Memorials of St Paul's Cathedral" Sinclair, W. p. 469: London; Chapman & Hall, Ltd; 1909.

- ^ page 284, St. Paul's The Cathedral Church of London 604–2004, Derek Keene. Arthur Burns & Andrew Saint (Editors), 2004 Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09276-8

- ^ A History of the Mason Lodge of Holyrood House (St.Luke's), No.44, holding of the Grand Lodge of Scotland with Roll of Members, 1734–1934, by Robert Strathern Lindsay, W.S., Edinburgh, 1935. Vol.II, p.628.

- ^ pages 255–256, The Life and Works of C.R. Cockerell, David Watkin, 1974, A. Zwemmer Ltd

- ^ "The Early Journal of C. R. Cockerell. Edited by his Son. (Longmans & Co.)". The Athenaeum (3963): 489. 10 October 1903.

- ^ John Newman; Nikolaus Pevsner (2006). Shropshire. Yale University Press. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-0-300-12083-7.

- ^ "CCockerell, Charles Robert". Irish Architectural Archive.

- ^ Cadw. "Newbridge Lodge (Grade I) (16872)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Walter Ison (1978). The Georgian buildings of Bristol. Kingsmead Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-901571-88-1.

- ^ pages 183 to 196, chapter XI 'The Path to Greatness: Cambridge University Library' in David Watkins: The Life and Work of C.R. Cockerell, 1974, Zwemmer

- ^ Historic England. "Woodbridge, Suffolk (1377059)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Walter Ison (1978). The Georgian buildings of Bristol. Kingsmead Press. p. 33. ISBN 0-901571-88-1.

- ^ Historic England. "Liverpool and London and Globe Building (1356318)". National Heritage List for England.

External links

[edit]- Works by Charles Robert Cockerell at Project Gutenberg

- http://www.racollection.org.uk/ixbin/hixclient.exe?submit-button=search&search-form=artist/artist_month_may2005.html&_IXSESSION_=F1tc7cZXMh7[permanent dead link]

- http://myweb.tiscali.co.uk/speel/arch/cockerel.htm Archived 31 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/people/A0812735.html

- Cockerell and the Grand Tour

- (in German) Antiquities of Athens and other places in Greece Sicily etc (London 1839). German edition Die Alterthümer von Athen from 1833, online at the University of Heidelberg

- "Archival material relating to Charles Robert Cockerell". UK National Archives.

- Profile on Royal Academy of Arts Collections

- 1788 births

- 1863 deaths

- 19th-century English architects

- 19th-century British archaeologists

- British neoclassical architects

- Archaeologists from London

- People educated at Westminster School, London

- People associated with the University of Wales, Lampeter

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

- Presidents of the Royal Institute of British Architects

- Royal Academicians

- People associated with the Ashmolean Museum

- Elgin Marbles

- Explorers of West Asia