Timbre

In music, timbre (/ˈtæmbər, ˈtɪm-, ˈtæ̃-/), also known as tone color or tone quality (from psychoacoustics), is the perceived sound quality of a musical note, sound or tone. Timbre distinguishes different types of sound production, such as choir voices and musical instruments. It also enables listeners to distinguish different instruments in the same category (e.g., an oboe and a clarinet, both woodwind instruments).

In simple terms, timbre is what makes a particular musical instrument or human voice have a different sound from another, even when they play or sing the same note. For instance, it is the difference in sound between a guitar and a piano playing the same note at the same volume. Both instruments can sound equally tuned in relation to each other as they play the same note, and while playing at the same amplitude level each instrument will still sound distinctively with its own unique tone color. Experienced musicians are able to distinguish between different instruments of the same type based on their varied timbres, even if those instruments are playing notes at the same fundamental pitch and loudness.[citation needed]

The physical characteristics of sound that determine the perception of timbre include frequency spectrum and envelope. Singers and instrumental musicians can change the timbre of the music they are singing/playing by using different singing or playing techniques. For example, a violinist can use different bowing styles or play on different parts of the string to obtain different timbres (e.g., playing sul tasto produces a light, airy timbre, whereas playing sul ponticello produces a harsh, even and aggressive tone). On electric guitar and electric piano, performers can change the timbre using effects units and graphic equalizers.

Synonyms

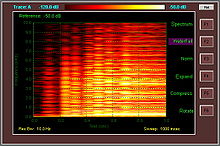

[edit]Tone quality and tone color are synonyms for timbre, as well as the "texture attributed to a single instrument". However, the word texture can also refer to the type of music, such as multiple, interweaving melody lines versus a singable melody accompanied by subordinate chords. Hermann von Helmholtz used the German Klangfarbe (tone color), and John Tyndall proposed an English translation, clangtint, but both terms were disapproved of by Alexander Ellis, who also discredits register and color for their pre-existing English meanings.[1] Determined by its frequency composition, the sound of a musical instrument may be described with words such as bright, dark, warm, harsh, and other terms. There are also colors of noise, such as pink and white. In visual representations of sound, timbre corresponds to the shape of the image,[2] while loudness corresponds to brightness; pitch corresponds to the y-shift of the spectrogram.

ASA definition

[edit]The Acoustical Society of America (ASA) Acoustical Terminology definition 12.09 of timbre describes it as "that attribute of auditory sensation which enables a listener to judge that two nonidentical sounds, similarly presented and having the same loudness and pitch, are dissimilar", adding, "Timbre depends primarily upon the frequency spectrum, although it also depends upon the sound pressure and the temporal characteristics of the sound".[3]

Attributes

[edit]Many commentators have attempted to decompose timbre into component attributes. For example, J. F. Schouten (1968, 42) describes the "elusive attributes of timbre" as "determined by at least five major acoustic parameters", which Robert Erickson finds, "scaled to the concerns of much contemporary music":[4]

- Range between tonal and noiselike character

- Spectral envelope

- Time envelope in terms of rise, duration, and decay (ADSR, which stands for "attack, decay, sustain, release")

- Changes both of spectral envelope (formant-glide) and fundamental frequency (micro-intonation)

- Prefix, or onset of a sound, quite dissimilar to the ensuing lasting vibration

An example of a tonal sound is a musical sound that has a definite pitch, such as pressing a key on a piano; a sound with a noiselike character would be white noise, the sound similar to that produced when a radio is not tuned to a station.

Erickson gives a table of subjective experiences and related physical phenomena based on Schouten's five attributes:[5]

| Subjective | Objective |

| Tonal character, usually pitched | Periodic sound |

| Noisy, with or without some tonal character, including rustle noise | Noise, including random pulses characterized by the rustle time (the mean interval between pulses) |

| Coloration | Spectral envelope |

| Beginning/ending | Physical rise and decay time |

| Coloration glide or formant glide | Change of spectral envelope |

| Microintonation | Small change (one up and down) in frequency |

| Vibrato | Frequency modulation |

| Tremolo | Amplitude modulation |

| Attack | Prefix |

| Final sound | Suffix |

See also Psychoacoustic evidence below.

Harmonics

[edit]

The richness of a sound or note a musical instrument produces is sometimes described in terms of a sum of a number of distinct frequencies. The lowest frequency is called the fundamental frequency, and the pitch it produces is used to name the note, but the fundamental frequency is not always the dominant frequency. The dominant frequency is the frequency that is most heard, and it is always a multiple of the fundamental frequency. For example, the dominant frequency for the transverse flute is double the fundamental frequency. Other significant frequencies are called overtones of the fundamental frequency, which may include harmonics and partials. Harmonics are whole number multiples of the fundamental frequency, such as ×2, ×3, ×4, etc. Partials are other overtones. There are also sometimes subharmonics at whole number divisions of the fundamental frequency. Most instruments produce harmonic sounds, but many instruments produce partials and inharmonic tones, such as cymbals and other indefinite-pitched instruments.

When the tuning note in an orchestra or concert band is played, the sound is a combination of 440 Hz, 880 Hz, 1320 Hz, 1760 Hz and so on. Each instrument in the orchestra or concert band produces a different combination of these frequencies, as well as harmonics and overtones. The sound waves of the different frequencies overlap and combine, and the balance of these amplitudes is a major factor in the characteristic sound of each instrument.

William Sethares wrote that just intonation and the western equal tempered scale are related to the harmonic spectra/timbre of many western instruments in an analogous way that the inharmonic timbre of the Thai renat (a xylophone-like instrument) is related to the seven-tone near-equal tempered pelog scale in which they are tuned. Similarly, the inharmonic spectra of Balinese metallophones combined with harmonic instruments such as the stringed rebab or the voice, are related to the five-note near-equal tempered slendro scale commonly found in Indonesian gamelan music.[6]

Envelope

[edit]

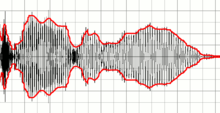

The timbre of a sound is also greatly affected by the following aspects of its envelope: attack time and characteristics, decay, sustain, release (ADSR envelope) and transients. Thus these are all common controls on professional synthesizers. For instance, if one takes away the attack from the sound of a piano or trumpet, it becomes more difficult to identify the sound correctly, since the sound of the hammer hitting the strings or the first blast of the player's lips on the trumpet mouthpiece are highly characteristic of those instruments. The envelope is the overall amplitude structure of a sound.

In music history

[edit]Instrumental timbre played an increasing role in the practice of orchestration during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Berlioz[7] and Wagner[8] made significant contributions to its development during the nineteenth century. For example, Wagner's "Sleep motif" from Act 3 of his opera Die Walküre, features a descending chromatic scale that passes through a gamut of orchestral timbres. First the woodwind (flute, followed by oboe), then the massed sound of strings with the violins carrying the melody, and finally the brass (French horns).

Debussy, who composed during the last decades of the nineteenth and the first decades of the twentieth centuries, has been credited with elevating further the role of timbre: "To a marked degree the music of Debussy elevates timbre to an unprecedented structural status; already in Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune the color of flute and harp functions referentially".[9] Mahler's approach to orchestration illustrates the increasing role of differentiated timbres in music of the early twentieth century. Norman Del Mar describes the following passage from the Scherzo movement of his Sixth Symphony, as "a seven-bar link to the trio consisting of an extension in diminuendo of the repeated As… though now rising in a succession of piled octaves which moreover leap-frog with Cs added to the As.[10] The lower octaves then drop away and only the Cs remain so as to dovetail with the first oboe phrase of the trio." During these bars, Mahler passes the repeated notes through a gamut of instrumental colors, mixed and single: starting with horns and pizzicato strings, progressing through trumpet, clarinet, flute, piccolo and finally, oboe:

(See also Klangfarbenmelodie.)

In rock music from the late 1960s to the 2000s, the timbre of specific sounds is important to a song. For example, in heavy metal music, the sonic impact of the heavily amplified, heavily distorted power chord played on electric guitar through very loud guitar amplifiers and rows of speaker cabinets is an essential part of the style's musical identity.

Psychoacoustic evidence

[edit]Often, listeners can identify an instrument, even at different pitches and loudness, in different environments, and with different players. In the case of the clarinet, acoustic analysis shows waveforms irregular enough to suggest three instruments rather than one. David Luce suggests that this implies that "[C]ertain strong regularities in the acoustic waveform of the above instruments must exist which are invariant with respect to the above variables".[11] However, Robert Erickson argues that there are few regularities and they do not explain our "...powers of recognition and identification." He suggests borrowing the concept of subjective constancy from studies of vision and visual perception.[12]

Psychoacoustic experiments from the 1960s onwards tried to elucidate the nature of timbre. One method involves playing pairs of sounds to listeners, then using a multidimensional scaling algorithm to aggregate their dissimilarity judgments into a timbre space. The most consistent outcomes from such experiments are that brightness or spectral energy distribution,[13] and the bite, or rate and synchronicity[14] and rise time,[15] of the attack are important factors.

Tristimulus timbre model

[edit]The concept of tristimulus originates in the world of color, describing the way three primary colors can be mixed together to create a given color. By analogy, the musical tristimulus measures the mixture of harmonics in a given sound, grouped into three sections. It is basically a proposal of reducing a huge number of sound partials, which can amount to dozens or hundreds in some cases, down to only three values. The first tristimulus measures the relative weight of the first harmonic; the second tristimulus measures the relative weight of the second, third, and fourth harmonics taken together; and the third tristimulus measures the relative weight of all the remaining harmonics:[16][17][page needed]

However, more evidence, studies and applications would be needed regarding this type of representation, in order to validate it.

Brightness

[edit]The term "brightness" is also used in discussions of sound timbres, in a rough analogy with visual brightness. Timbre researchers consider brightness to be one of the perceptually strongest distinctions between sounds[14] and formalize it acoustically as an indication of the amount of high-frequency content in a sound, using a measure such as the spectral centroid.

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Erickson 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Abbado, Adriano (1988). "Perceptual Correspondences: Animation and Sound". MS Thesis. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. p. 3.

- ^ Acoustical Society of America Standards Secretariat (1994). "Acoustical Terminology ANSI S1.1–1994 (ASA 111-1994)". American National Standard. ANSI / Acoustical Society of America.

- ^ Erickson 1975, p. 5.

- ^ Erickson 1975, p. 6.

- ^ Sethares, William (1998). Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale]. Berlin, London, and New York: Springer. pp. 6, 211, 318. ISBN 3-540-76173-X.

- ^ Macdonald, Hugh. (1969). Berlioz Orchestral Music. BBC Music Guides. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. p. 51. ISBN 9780563084556.

- ^ Latham, Peter. (1926) "Wagner: Aesthetics and Orchestration". Gramophone (June): [page needed].

- ^ Samson, Jim (1977). Music in Transition: A Study of Tonal Expansion and Atonality, 1900–1920. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-02193-9.

- ^ Del Mar, Norman (1980). Mahler’s Sixth Symphony: A Study. London: Eulenburg.

- ^ Luce, David A. (1963). "Physical Correlates of Nonpercussive Musical Instrument Tones", Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Erickson 1975, p. 11.

- ^ Grey, John M. (1977). "Multidimensional perceptual scaling of musical timbres". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 61 (5). Acoustical Society of America (ASA): 1270–1277. Bibcode:1977ASAJ...61.1270G. doi:10.1121/1.381428. ISSN 0001-4966. PMID 560400.

- ^ a b Wessel, David (1979). "Low Dimensional Control of Musical Timbre". Computer Music Journal 3:45–52. Rewritten version, 1999, as "Timbre Space as a Musical Control Structure".

- ^ Lakatos, Stephen (2000). "A common perceptual space for harmonic and percussive timbres". Perception & Psychophysics. 62 (7). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 1426–1439. doi:10.3758/bf03212144. ISSN 0031-5117. PMID 11143454. S2CID 44778763.

- ^ Peeters, G. (2003) “A Large Set of Audio Features or Sound Description (Similarity and Classification) in the CUIDADO Project”.[full citation needed]

- ^ Pollard, H. F., and E. V. Jansson (1982) A Tristimulus Method for the Specification of Musical Timbre. Acustica 51:162–71.

References

[edit]- American Standards Association (1960). American Standard Acoustical Terminology. New York: American Standards Association.

- Dixon Ward, W. (1965). "Psychoacoustics". In Audiometry: Principles and Practices, edited by Aram Glorig, 55. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins Co. Reprinted, Huntington, N.Y.: R. E. Krieger Pub. Co., 1977. ISBN 0-88275-604-4.

- Dixon Ward, W. (1970) "Musical Perception". In Foundations of Modern Auditory Theory vol. 1, edited by Jerry V. Tobias, [page needed]. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-691901-1.

- Erickson, Robert (1975). Sound Structure in Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02376-5.

- McAdams, Stephen, and Albert Bregman (1979). "Hearing Musical Streams". Computer Music Journal 3, no. 4 (December): 26–43, 60.

- Schouten, J. F. (1968). "The Perception of Timbre". In Reports of the 6th International Congress on Acoustics, Tokyo, GP-6-2, 6 vols., edited by Y. Kohasi, [full citation needed]35–44, 90. Tokyo: Maruzen; Amsterdam: Elsevier.