Battle of Legnano

| Battle of Legnano | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Guelphs and Ghibellines | |||||||

A clash between knights, capital 12th century, Pavia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Lombard League | Holy Roman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Guido da Landriano | Frederick I Barbarossa | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 [nb 1] |

3,000 [nb 2] (incl. 2,500 knights) | ||||||

Location within Italy | |||||||

The battle of Legnano was a battle between the imperial army of Frederick Barbarossa and the troops of the Lombard League on 29 May 1176, near the town of Legnano, in present-day Lombardy, Italy.[6][7] Although the presence of the enemy nearby was already known to both sides, they suddenly met without having time to plan any strategy.[8][9]

The battle was crucial in the long war waged by the Holy Roman Empire in an attempt to assert its power over the municipalities of northern Italy,[8] which decided to set aside their mutual rivalries and join in a military alliance symbolically led by Pope Alexander III, the Lombard League.[10]

The battle ended the fifth and last descent into Italy of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa,[6] who after the defeat tried to resolve the Italian question by adopting a diplomatic approach. This resulted a few years later in the Peace of Constance (25 June 1183), with which the Emperor recognized the Lombard League and made administrative, political, and judicial concessions to the municipalities, officially ending his attempt to dominate northern Italy.[11][12]

The battle is alluded to in the Canto degli Italiani by Goffredo Mameli and Michele Novaro, which reads: «From the Alps to Sicily, Legnano is everywhere» in memory of the victory of Italian populations over foreign ones.[13] Thanks to this battle, Legnano is the only city, besides Rome, to be mentioned in the Italian national anthem.[13] In Legnano, to commemorate the battle, the Palio di Legnano takes place annually from 1935, on the last Sunday of May.[14] In the institutional sphere, the date of 29 May was chosen as the regional holiday of Lombardy.[15]

Background

[edit]Historical context

[edit]

The clash between the municipalities of northern Italy and imperial power originated in the struggle for investitures,[16] or in that conflict which involved, in the 11th and the 12th centuries, the Papacy, the Holy Roman Empire, and their respective factions, the so-called "Guelphs and Ghibellines", respectively.[16] At times it was a dispute so bitter that several municipalities in northern Italy came to dismiss their bishops on the charge of simony, inasmuch as they had been invested in their offices by the emperor and not by the Pope.[16]

The dispute about investitures was not the only source of friction between the Empire and the municipalities of northern Italy. A crisis of feudalism arose with the economic growth of northern Italian cities and their emerging desire to free themselves from imperial administration.[16] Furthermore, the Italian territories of the Holy Roman Empire were distinctly different from the Germanic ones[17] in socioeconomic and cultural aspects, and were not sympathetic to imperial power wielded by an authority of German lineage.[17] Moreover, the nobility of the Italian territories dominated by the Empire were much less (and progressively less) involved in the administrative functions of the city-dominated regions, than the nobility were in German lands.[17] Because of the frictions that arose in the 11th and the 12th centuries, the cities of northern Italy experienced a rising ferment that led to the birth of a new form of local self-government based on an elective collegial body with administrative, judicial, and security functions, and which in turn designated city consuls: the medieval commune.[18]

This institutional evolution was contemporary with the investiture struggle.[19] When a city's bishop, who had traditionally exerted a strong influence on the civil matters of the municipality,[20] became largely preoccupied with the contest between Empire and Papacy, the citizens were stimulated, and in some ways obliged, to seek a form of self-government that could act independently in times of serious difficulty.[19] Citizens became increasingly aware of the public affairs of their own municipality and disinclined to accept the ecclesiastical and feudal structures, with their rigid and hierarchical management of the government.[21] The change that led to a collegial management of public administration was rooted in the Lombard domination of northern Italy;[22] this Germanic people was in fact accustomed to settling the most important questions (which were usually of military nature) through an assembly presided over by the king and composed of the most valiant soldiers, the "gairethinx"[23] or "arengo".[22][nb 3] City consuls generally came from the increasingly dominant (merchant and professional) classes of a city;[24] although the duration of a consul's mandate was only one year, and there was a certain turnover of individuals in the positions, a communal administration sometimes amounted to a coterie of leading families that shared municipal power in oligarchic fashion.[24] In any case the northern Italian cities gradually ceased to recognize feudal institutions, which now seemed outdated.[8]

Moreover, previous emperors, for various vicissitudes, adopted for a certain period an attitude of indifference towards the issues of northern Italy,[16] taking more care to establish relations that provided for supervision of the Italian situation rather than the effective exercise of power.[25] As a consequence, imperial power did not prevent the expansionist aims of the various municipalities in the surrounding territories and other towns,[25] and cities began taking up arms against each other in contests to achieve regional hegemony.[16]

Frederick Barbarossa, on the other hand, repudiated the policy of his predecessors by attempting to restore imperial control over the northern Italian municipalities, also on the basis of the requests of some of the latter, who repeatedly asked for imperial intervention to limit Milan's desire for supremacy:[26][16] in 1111 and 1127 the city conquered, respectively, Lodi and Como, forcing Pavia, Cremona and Bergamo to passivity.[27]

To make matters worse the relations between the Empire and the municipalities were further soured by the harsh measures implemented by imperial authorities against the Milanese region.[28] Of these, two contributed the most to fuel anti-imperial sentiment: to try to interrupt the supplies in Milan during one of his descents in Italy, in 1160, the emperor devastated the area north of the city destroying the crops and fruit trees of farmers.[29] In particular, in fifteen days Barbarossa destroyed the countryside of Vertemate, Mediglia, Verano, Briosco, Legnano, Nerviano, Pogliano and Rho.[8] The second event was instead linked to the measures taken by Frederick Barbarossa after the surrender of Milan (1162):[29] the imperial vicar who administered the Milanese countryside after the defeat of Milan forced the farmers of the area to pay a heavy annual tax of foodstuffs for the emperor, which made the population increasingly hostile to imperial power.[30]

The first three descents of Frederick Barbarossa in Italy

[edit]To try to pacify northern Italy and restore imperial power, Frederick Barbarossa crossed the Alps at the head of his army five times. The first descent, which began in the autumn of 1154 and led only 1,800 men,[16][31][32] led the king to besiege and conquer the riotous Asti, Chieri and Tortona and to attack some castles of the Milanese countryside, but not the capital of Milan, given that he did not have sufficient forces.[33][34] This campaign continued with the convocation of diet of Roncaglia, with which Frederick re-established imperial authority, nullifying, among other things, the conquests made by Milan in previous years, especially with regard to Como and Lodi.[33] The first part of that journey continued along the Via Francigena[35] and ended in Rome with the coronation of Frederick Barbarossa as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Adrian IV (18 June 1155[36]).[31][37][38] During his stay in Rome, Frederick, who had left from the north with the title of King of Germany, was harshly contested by the people of the city;[39] in response, the emperor reacted by stifling the revolt in blood.[39] Following this episode, and to Frederick's military campaign, the relations between the Holy Roman Empire and the Papacy began to crack.[39] During the return trip to Germany, the emperor destroyed Spoleto, accused of having paid the fodro, that is, the taxes to be paid to the sovereign, with a false currency.[39] Already during this first descent, the difference between Frederick and his predecessors was felt.[39] In fact, Barbarossa showed a strong aversion to municipal autonomies: his will was to restore effective power over northern Italy.[39]

The second descent, which began in June 1158, was originated by the rebelliousness of Milan and the allied municipalities to accept imperial power.[31][40] This long expedition began with the attack of Frederick Barbarossa in Milan and his allies of the Milanese countryside:[41] after defeating Brescia, which was a Milanese company, and having freed Lodi from the Milanese yoke, Barbarossa directed the attack to the Milanese capital, who agreed to surrender (8 September 1158) to avoid a long and bloody siege.[42] Milan again lost the conquests made in previous years (Como, Pavia, Seprio and Brianza),[43] but it was not razed.[44] Frederick Barbarossa, then, summoned a second diet to Roncaglia (autumn 1158[45]) where he reiterated the imperial dominion over the municipalities of northern Italy, with the authority of the sovereign that imposed itself on that of the local institutions,[43] establishing, among other things, that the regalie were entirely paid to the sovereign.[46] The proclamations of this second diet of Roncaglia had disruptive effects on the Italian communes, which immediately rebelled.[47] After receiving reinforcements from Germany and having conquered several riotous municipalities in northern Italy during a military campaign that lasted a few years, Barbarossa turned its attention to Milan, which was first besieged in 1162 and then, after its surrender (1 March[48]), completely destroyed.[49][50] A similar fate fell on several cities allied to Milan.[51] Frederick then exacerbated the grip of imperial power on Italian cities, going beyond the provisions decided during Roncaglia's second diet:[52] he set up a bureaucratic structure run by officials who responded directly to the emperor instead of the municipal autonomies, which were virtually suppressed,[52] and established an imperial-nominated podestà at the head of the rebel cities.[8][53] Meanwhile, Pope Adrian IV died and his successor, Pope Alexander III, soon proved to be in solidarity with the Italian municipalities and particularly hostile to the emperor.[31]

In 1163 the rebellion of some cities in northeastern Italy forced Frederick Barbarossa to descend for the third time in Italy in a military campaign that ended up in a stalemate, above all against the Veronese League, which in the meantime had formed between some cities of the March of Verona.[6][54] With pacific Lombardy,[55] Frederick in fact preferred to postpone the clash with the other municipalities of northern Italy due to the numerical scarcity of his troops and then, after having verified the situation, he returned to Germany.[54]

The fourth military campaign in Italy and the Lombard League

[edit]

At the end of 1166 the emperor went to Italy for the fourth time at the head of a powerful army.[56] To avoid the Marca of Verona, after having crossed the Alps from the Brenner Pass, instead of going along the usual Adige Valley, Barbarossa turned towards Val Camonica;[56][57] its objective was not, however, the attack on the rebellious Italian communes, but the Papacy.[58] In fact, Frederick sided with the Antipope Paschal III, who in the meantime had ousted the legitimate pontiff, Alexander III, from Peter's throne;[59] the latter, in 1165, after having obtained the recognition of the other European sovereigns, had returned to Rome, but Barbarossa, mindful of the role that his predecessors had on papal appointments, decided to intervene directly.[59] As a test of strength, and for demonstration purposes, Frederick attacked some cities in northern Italy,[58] reaching Rome victorious, but an epidemic that spread among the ranks of the imperial army (perhaps of malaria) and which also affected the emperor himself, forced him to leave Rome, which in the meantime had surrendered, and to return precipitously to northern Italy in search of reinforcements (August 1167).[60]

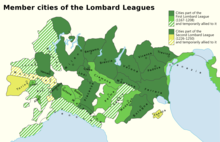

A few months before the epidemic that struck the imperial army, the municipalities of northern Italy had joined forces in the Lombard League,[31] a military union whose Latin name was Societas Lombardiae.[61] According to the traditional narrative the municipalities sealed their alliance on 7 April 1167 with the oath of Pontida;[62] this event, however, is questioned by historians for its lack of mention in contemporary chronicles and because the first mention of the oath is late, given that it appears in a document dated 1505.[63] On 1 December 1167 the Lombard League expanded considerably with the accession of the municipalities of the Lega Veronese.[64] Arrived in northern Italy, Frederick decided to face the League, but finding himself in a stalemate that was caused by some failed sieges and by the constant growth of the number of cities that adhered to the municipal military alliance,[65] he decided to postpone the confrontation and to return to Germany (1168).[66] After the emperor's departure, the role of the Lombard League was limited to the diplomatic or military resolution of the diatribes that periodically broke out between the municipalities belonging to the alliance.[67]

Shortly after Barbarossa returned to Germany, the League founded a new city, Alessandria, named in honor of Pope Alexander III, who sided with the Italian municipalities[68][69] so that the municipal military coalition was symbolically headed by the same Pope.[10][70] The foundation of a new city without the consent of the imperial authority was a serious setback to Frederick Barbarossa, who decided to definitively resolve the Italian question.[71]

The fifth and last descent

[edit]

In 1174 Frederick Barbarossa, to try to resolve the situation once and for all,[72] went down to Italy for the fifth time with a powerful army of about 10,000 men.[31][73] Instead of crossing the Alps from the usual Brenner, guarded by the League,[72] the emperor had passed from Savoy thanks to the support of Count Humbert III.[74] In the first phase of the campaign he succeeded in easily subjugating some cities of northwestern Italy, trying without luck to conquer also Alessandria (1174–1175).[75] After this unfortunate siege, with the exhausted army,[76] Frederick went to Pavia (April 1175), his ally and shortly before sacked by the municipal armies,[77] to try to find an agreement with the army of the League, but without success.[75] During the negotiations the emperor thought, at a certain point, that the agreement was close and therefore dismissed most of his army;[78] the negotiations, however, failed in May 1175 and the armies prepared themselves again for the war.[79]

Realizing the mistake he made, which would later prove decisive, the emperor met his cousin Henry the Lion and other feudal lords in Chiavenna between January and February 1176 with the aim of asking for reinforcements to continue his campaign.[78][80] When Henry denied him these, Frederick turned to his wife Beatrice of Burgundy; Rainald of Dassel, the archbishop of Cologne and Archchancellor; and Wichmann von Seeburg, archbishop of Magdeburg, asking for additional troops to be sent to Italy;[81] after receiving the support of the latter, he moved to Bellinzona to wait for them.[82] Upon the arrival of the troops, Frederick realized, however, that their number was much lower than expected, since they consisted only of a number of knights including, according to the discordant sources of the time, between 1,000 and 2,000 units[6][81] (the latter, according to most historians, is the most probable[83]).

Despite the insufficient number of reinforcements coming from Germany and other Italian allies,[84] the emperor decided to leave the alpine valleys resuming the march from Como to Pavia, both of his allies, in a hostile territory but characterized by the presence of vast areas covered with an impenetrable forest that allowed a relatively safe journey.[85] His goal was to meet with the rest of his militias and to clash with the municipal troops in the Milanese or in Alessandria;[86][81] Frederick Barbarossa was in fact certain that a march in forced stages towards Pavia could have prevented the municipal troops from intercepting it.[86] The Lombard League, on the other hand, decided to engage in battle with the imperial army as soon as possible to prevent the reunification of the Teutonic armies;[86][81] this despite being still in reduced ranks (15,000 men[87]), given that he could not count on all the military forces specified in the various cities forming part of the alliance (30,000 men[88]), which were in fact still converging on Milan.[89]

The Lombard League was headed by the Cremonese Anselmo da Dovara and by the Vicentine Ezzelino I da Romano representing the two souls of the coalition, the Lombard and the Venetian.[90] The military operations of the municipal troops, on this occasion, were instead guided by the Milanese Guido da Landriano, former consul of the Milanese capital, rector of the Lombard League as well as an expert knight.[91]

Stages of battle

[edit]Frederick Barbarossa in Cairate

[edit]

On the night of 28-29 May 1176, during the descent towards Pavia, Frederick Barbarossa was with his troops at the monastery of the Benedictine nuns of Cairate[61] for a stop which later proved to be fatal, since it caused a delay compared to the contemporaneous moves of the Lombard League.[8][89] The emperor probably spent the night in Castelseprio in the manor of the counts of the homonymous county, who were bitter enemies of Milan.[92] Barbarossa decided to stop in Cairate to cross the River Olona, the only natural barrier that separated it from the faithful Pavia, trusting to have the possibility to enter the area controlled by the allied city after having traveled the remaining 50 km in a horse day.[93]

Overall, according to most historians,[83] the imperial army encamped in Cairate was formed by 3,000 men (2,000 of whom were reinforcements from Germany),[83] the vast majority of whom were heavy cavalry,[87] who was able, if necessary, to fight on foot.[94] Despite the numerical disparity, the extent of the Teutonic army was highly respected, given that it consisted of professional soldiers.[83] The army of the League was instead mainly made up of private citizens who were recruited in case of need;[95] the knights of the League, given the high cost of the steed and armor, were of high social extraction, while the infantry were mostly peasants and citizens from the low social classes.[96]

The Carroccio in Legnano

[edit]

However, the information regarding Barbarossa encamped in Cairate did not reach the leaders of the Lombard League, who were convinced that the emperor was distant, still in Bellinzona waiting for the reinforcement troops.[8][97] For this reason, the Carroccio, the emblem of the autonomy of the municipalities belonging to the Lombard League carrying the cross of Aribert,[6][98] escorted by a few hundred men of the League, was transferred from Milan to Legnano, leaving from the capital of Milan from Porta Romana,[99] and then up the Olona to its final destination.[9][100] In Legnano the Carroccio was placed along a slope flanking the river, presumably wooded,[101] to have a natural defense on at least one side, that traced by the stream.[7]

In this way, Barbarossa, who was expected along the river coming from Castellanza, would have been obliged to attack the municipal army in a situation of disadvantage, having to go back to this depression.[102] This choice turned out to be wrong: in fact Barbarossa arrived from Borsano (nowadays frazione (hamlet) of Busto Arsizio), that is from the opposite side, forcing the municipal troops to resist around the Carroccio with the escape road blocked by the Olona.[102] Another possible reason that led the municipal troops to position the Carroccio in Legnano was to anticipate Barbarossa, still believed to be far away, by making an incursion into the Seprio with the aim of preventing a new alliance between the two: the Seprio was in fact a historically connected territory with the emperor together with another area of Lombardy, the Martesana.[103]

The Lombard League troops took possession of the area between Legnano, Busto Arsizio, and Borsano.[104] The remaining part of the army, which on the whole was formed by about 15,000 men (3,000 of whom were knights, while 12,000 were infantry[87]), followed with considerable detachment along the road between the Lombard capital and Legnano. The decision to place the Carroccio in Legnano was not accidental. At the time the village represented an easy access for those coming from the north to the Milanese countryside, given that it was located at the mouth of the Valle Olona, which ends at Castellanza;[103] this passage had therefore to be closed and strenuously defended to prevent the attack on Milan, which was also facilitated by the presence of an important road that existed since Roman times, the Via Severiana Augusta, which connected Mediolanum (the modern Milan) with the Verbanus Lacus (Lake Verbano, or Lake Maggiore[105]), and from there to the Simplon Pass (lat. Summo Plano).[106] His journey was then taken up by Napoleon Bonaparte to build the Simplon state road.[107]

For this reason, in Legnano there was a high medieval fortification, the castle of the Cotta, which was built at the time of the Hungarian raids[108] and which was later used during the battle of Legnano as a military outpost.[109] Later, the castle of the Cotta was replaced, as a defensive bulwark of Legnano, by the Castle Visconteo, which rises further south along the Olona. The Cotta castle was flanked by a defensive system formed by walls and a flooded moat that encircled the inhabited center, and by two access gates to the village: medieval Legnano thus appeared as a fortified citadel.[109][110]

A second reason that explains the positioning of the Carroccio in Legnano lay in the fact that the Legnanese was a territory not hostile to the troops of the Lombard League, given that the population of the area was still mindful of the devastation operated by Frederick Barbarossa a few years earlier;[30] these people would also have provided logistical support to the troops of the League.[111] From a strategic point of view, in Legnano the municipal army was therefore in a position that would have prevented the emperor from making the most logical moves: to attack Milan or reach Pavia.[93]

The first contact between the armies in Borsano

[edit]

After spending the night in Cairate, Frederick Barbarossa resumed the march on Pavia heading towards the Ticino.[92] Meanwhile, some avant-gardes of the Lombard League army stationed in Legnano, formed by 700 knights, broke away from the main army and searched the territory between Borsano and Busto Arsizio.[106] According to other sources, the knights instead controlled the area between Borsano and Legnano, in other words, the modern-day districts of Ponzella and Mazzafame.[6][112]

At 3 miles (about 4.5 km) from Legnano, near Cascina Brughetto,[113] the 700 municipal knights on the track crossed—just outside a forest—300 knights of the imperial army on patrol, which represented only the vanguards of Frederick's troops.[7][114] Being numerically superior, the Knights of the League attacked the imperial column and succeeded, at least initially, in gaining the upper hand.[106] Immediately after the first clashes, Barbarossa arrived with the bulk of the army and charged the municipal troops.[101][114] Some chroniclers of the time report that Barbarossa's advisers had suggested to the emperor to stall for a new strategy, but the sovereign would have refused to take advantage of the numerical superiority[101][106] and not to be forced to retreat towards hostile territories;[115] furthermore, a retreat would have affected the prestige of the emperor.[115] The fate of the battle, therefore, reversed and the imperial troops forced the first rows of the municipal army to back off in confusion.[101][114]

The strong impact then forced the municipal knights to retreat towards Milan, leaving the soldiers alone who were in Legnano to defend the Carroccio.[101] Barbarossa therefore decided to attack the latter with the cavalry, given that it was defended only by the infantry—according to the canons of the time considered to be clearly inferior to the cavalry[116]—and to a small number of militias on horseback.[106]

The defense of the Carroccio in Legnano and the epilogue

[edit]

At this point an exceptional event occurred[106] with respect to the traditional dominance of cavalry on infantry of that period. In Legnano the municipal infantry, with the few remaining knights,[100] after being attacked by Barbarossa, settled around the Carroccio (maintaining a certain distance from the symbol of their municipalities), organizing themselves on some defensive lines along a wide semicircle 2–3 km,[117] each of which consisted of soldiers protected by shields.[101][106] Between one shield and another the lances were then stretched, with the first row of foot soldiers fighting on their knees so as to form a jumble of spears aimed at the enemy.[118] During the fight, which lasted eight to nine hours from morning to three in the afternoon[119] and which was characterized by repeated charges punctuated by long pauses to make the armies repackage and refurbish,[120] the first two lines finally gave way, but the third resisted shocks.[7][106] According to other sources, the rows that capitulated were instead four, with a fifth and last that rejected the attacks.[101]

Meanwhile, the municipal troops who were retreating towards Milan met the bulk of the Lombard League army moving towards Legnano;[101] the municipal army, now reunified, after having reorganized moved towards Legnano and arrived at the point where the Carroccio was located attacked the imperial troops on the sides and from behind, who were already tired from the vain assaults on the Carroccio.[119][121] With the arrival of the cavalry, also the infantrymen around the communal cart passed to the counteroffensive.[119][121] Sensing that the heart of the battle was now around the Carroccio, Frederick Barbarossa, with his usual audacity, threw himself into the middle of the fray trying to encourage his troops, but without appreciable results.[119] In the heat of battle his horse was mortally wounded[122] and the emperor disappeared to the sight of the fighters;[123][124] in addition, the imperial army standard-bearer was killed, pierced by a spear.[119][123] The imperials, attacked on two sides, then began to become discouraged and faced a total defeat.[122][123]

The strategy of the imperials to resist until the evening and then, at the end of the battle, fall back to catch up and reorganize did not go well.[119] They tried to flee towards Ticino passing from Dairago and Turbigo,[100] but were pursued by the troops of the Lombard League[122][123] for eight miles.[123][124] The waters of the river were the theater of the last phases of the battle, which ended with the capture and killing of many soldiers of the imperial army[100][122] and with the sacking of the military camp of Frederick Barbarossa in Legnano.[124] The emperor himself found it difficult to escape capture and reach the faithful Pavia.[6][122]

After the battle, the Milanese wrote to the Bolognese, their allies in the League, a letter stating, among other things, that they had in custody, right in Milan, a conspicuous loot in gold and silver, the banner, the shield and the imperial spear, and a large number of prisoners, including Count Berthold I of Zähringen (one of the princes of the Empire), Philip of Alsace (one of the empress's grandchildren) and Gosvino of Heinsberg (the brother of the Archbishop of Cologne).[125][126]

Losses

[edit]

There are no precise data on the losses suffered by the two armies that faced each other in the battle of Legnano;[127] from the descriptions in our possession, however, it can be affirmed that the imperial ones were heavy,[128] while the losses attributable to the municipal army were quite slight.[127]

According to some studies conducted by Guido Sutermeister, part of the dead of the battle of Legnano were buried around the little church of San Giorgio, now no longer in existence, which once stood on the top of the hill of San Martino along the modern via Dandolo, in the near the church of San Martino in Legnano.[129][130]

Analysis of battle

[edit]From the military point of view, the battle of Legnano was a significant battle that involved a considerable number of men.[131] Other important battles fought in the same period in fact employed a comparable number of soldiers:[131] for example, 1,400 Aragonese knights and 800 French were involved in the Battle of Muret.[131]

At the strategic level, the clash between the two armies was carefully prepared by both factions.[131] Barbarossa meticulously chose the place to cross the Alps, deciding to wait for reinforcements and to cross the Alpine arch again centrally in place of the usual Brenner, to easily reach Pavia.[131] In fact, the second choice would have involved a much longer journey in enemy territory.[131] Moreover, shortening the journey to Alexandria, his real goal, he focused on the surprise effect, which he partly obtained.[132] Even the leaders of the Lombard League acted with foresight: to beat the emperor on time, they anticipated the times and moved towards Legnano to block the way towards the rest of his army, forcing him to fight in a territory known to them and therefore favorable.[132]

One of the most important phases of the battle was the strong resistance of the infantry around the Carroccio after the temporary retreat of the cavalry; under the emblem of the autonomy of their municipalities, the municipal infantry resisted against a militarily superior army and moreover on horseback.[6][133] The Carroccio also had a tactical function:[6] being a very important symbol, in case of folding, the municipal army would have been obliged to protect it at all costs, and so it happened that, just to stay around the wagon, the municipal infantry they organized themselves into a semicircle defensive system.[6] The position of the lances within this formation, all facing outwards, was certainly another reason for the victorious resistance, given that it constituted a defensive bulwark that could not be easily overcome[6] Furthermore, the municipal troops, grouped on a territorial basis, were linked by kinship or neighborhood relations, which contributed to further compacting the ranks.[120] In addition to fighting for their fellow soldiers, the municipal soldiers also fought for the freedom of their city and to defend their possessions and this led to a further stimulus to resistance against the enemy.[134]

This battle is one of the first examples in which the medieval infantry could demonstrate its tactical potential towards the cavalry.[133][135] The merit of the victory of the municipal troops must however also be shared with the light cavalry, which came later, which carried out the decisive charge against the imperials.[136]

Origins and places of battle

[edit]

At centuries of distance, given the scarcity of authentic information written by contemporary chroniclers at the events, it is difficult to establish precisely where the clashes took place.[137] The chronicles of the epoch that deal with the battle of Legnano are in fact short writings formed by a number of words between one hundred and two hundred;[137] the exception is the Life of Alexander III written by Boso Breakspeare, which reaches four hundred words.[137] On some occasions there is the problem of the distortion of toponyms made by the copyists of the time, who did not know the geography of the area.[7]

The contemporary sources that deal with the battle of Legnano are divided into three categories: the chronicles written by the Milanese or by the federated cities in the Lombard League, those written by the imperials or their allies and the ecclesiastical documents of the papal party.[138] The contemporary Milanese chronicles unanimously report that the battle was fought de, apud, iuxta, ad Lignanum or inter Legnanum et Ticinum.[139] Among them stands a document compiled by two anonymous chroniclers (Gesta Federici I imperatoris in Lombardy. Trad.: "The exploits of Emperor Frederick I in Lombardy"[140]), whose two parts of the text, written by an unknown reporter between 1154 and 1167 and the other completed by another anonymous in 1177, they were copied in 1230 by Sire Raul.[141] The annals of Brescia, of Crema, the Genoese chronicler Ottobono, Salimbene from Parma and the bishop of Crema[139] also report apud Legnanum. The contemporary chronicles of the imperial part, on the other hand, do not specify the places of the conflict but merely describe the events;[138] among the Teutonic documents, the most important are the annals of Cologne, the writings of Otto of Freising and the chronicles of Godfrey of Viterbo.[138] The most important contemporary ecclesiastical sources are the writings of the Archbishop of Salerno and the Life of Alexander III drafted by Boso Breakspeare,[138] with the first not referring to the indication of the places,[142] and the second that report the crippled toponym of Barranum.[92]

Among the sources after the battle, Bonvesin da la Riva, who wrote about a century after the fight, stated that the battle had taken place "inter Brossanum et Legnanum", while Goffredo da Bussero, a contemporary of Bonvesin de la Riva, reported that "imperator victus a Mediolanensisbus inter Legnanum et Borsanum".[92]

The first phase of the battle, which is connected to the initial clash between the two armies, seems to have taken place between Borsano and Busto Arsizio.[143][144] This thesis is supported, among other things, by the document of the two anonymous chroniclers, where it is said that:[145][146]

Then Saturday 29 May 1176, while the Milanese were at Legnano together with fifty knights from Lodi, about three hundred from Novara and Vercelli, about two hundred from Piacenza, with the militia of Brescia, Verona and the whole of the March [Trevigiana]. the infantry of Verona and Brescia were in the city, others were near by on the street and came to join the Milanese army – the Emperor Frederick was encamped with all the Comaschi near Cairate with about a thousand German knights, and it was said that they were two thousand he had brought across the valley of Disentis so secretly that none of the Lombards could have known. Indeed, when it was said that they were near Bellinzona, it seemed like a fairy tale. The emperor wanted to pass and go to Pavia, believing that the Pavesi should come to meet him. Instead they came, met the Milanese with the knights indicated above, between Borsano and Busto Arsizio, and a huge battle was attacked. The emperor put to flight the knights who were on one side near the Carroccio, so that almost all the Brescians and most of the others fled to Milan, as well as most of the best Milanese. The others stopped at the Carroccio with the Milan infantrymen and fought heroically. Finally the emperor was made to flee, almost all the Comaschi were captured, of the Germans many were taken and killed, many died in the Ticino.

— Anonymous reporters, The exploits of Emperor Frederick I in Lombardy

As for the final stages of the battle, which are connected to the defense of the Carroccio and the subsequent and resolute clashes between the two armies, the Life of Alexander III of Boso Breakspeare, contemporary with the battle,[137] provides an important indication:[7] in this text we indicate the toponyms, evidently crippled by the copyists, of Barranum and Brixianum, which could indicate Legnano and Borsano or Busto Arsizio and Borsano, and the precise distance between the site of the last phases of the battle and Milan, 15 miles (about 22 km), which is the exact distance between Legnano and the Lombard capital.[7][92] This distance of 15 miles was then used to refer to Legnano also in subsequent documents.[92][97] In fact, in the Life of Alexander III we read that:[147]

[The Milanese] settled, in large numbers, in a place suitable for them, between Barrano and Brissiano, around eight o'clock, 15 miles from the city.

— Boso Breakspeare, Life of Alexander III

The same source also mentions the distance of 3 miles (about 4.5 km) from Legnano in reference to the first contact of the two armies, confirming the hypothesis that this phase of the clash took place between Borsano and Busto Arsizio.[101][148] The same document states that:[149]

Then they sent forward, towards Como, 700 soldiers to know on which side their powerful and very strong adversary advanced. There they met 300 Germanic soldiers, for about three miles, whose traces Frederick trodden with the whole army, ready to fight.

— Boso Breakspeare, Life of Alexander III

Regarding the identification of the place where the troops of the Lombard League on the run met the remaining part of the army, the sources are conflicting.[150] The chronicles of Boso Breakspeare report in fact that the crossing of the two armies took place at half a mile (about 700 m) from the Carroccio:[101][151]

The Lombards were forced, in spite of themselves, to flee and, wishing to find refuge with the Milanese carroccio, could not remain to face the pursuer, but were forced to flee with the many other fugitives, beyond the carroccio, for half a mile.

— Boso Breakspeare, Life of Alexander III

The annals of Piacenza instead report that the contact occurred near Milan:[101][152]

The emperor, however, put the Milan militias to flight as far as the Carroccio, while most of the Lombard militias fled to the city.

— Annals of Piacenza

As regards the exact location of the Carroccio in reference to the current topography of Legnano, one of the chronicles of the clash, the Cologne Annals, contain important information:[153]

The Lombards, ready to win or die on the field, placed their army inside a large pit, so that when the battle was in full swing, no one could escape.

— Annals of Cologne

This would suggest that the Carroccio was located on the edge of a steep slope flanking the Olona, so that the imperial cavalry, whose arrival was expected along the river, would have been forced to attack the center of the League's army Lombard climbing up the escarpment.[154] Considering the evolution of the clash, this could mean that the crucial phases in defense of the Carroccio have been fought on the territory of the Legnanese contrada of San Martino (more precisely, near the 15th century church of the same name, which in fact dominates a slope that descends towards the Olona[102]) or of the Legnanese quarter of Costa San Giorgio, since in another part of the neighboring areas it is not possible to identify another depression with the characteristics suitable for its defense.[98][154] Considering the last hypothesis mentioned, the final clash could also have taken place on part of the territory now belonging to the Legnanese contrade of Sant'Ambrogio and San Magno (between the quartier of "Costa of San Giorgio" and the Olona is still present today a steep slope: this slope was later included in the Parco castello) and to the municipality of San Giorgio su Legnano.[98][154]

A popular legend tells that at that time a tunnel put San Giorgio su Legnano in communication with the Visconti castle of Legnano and that for this tunnel Frederick Barbarossa managed to escape and save himself after the defeat.[155] Towards the end of the 20th century, during some excavations, sections of a very ancient tunnel were actually found: the first was found not far from San Giorgio su Legnano, while the second section was discovered in Legnano. Both were immediately blocked by the municipal administration for security reasons.[156] During some excavations carried out in 2014 at the Visconti castle in Legnano, the entrance to another tunnel was identified.[157]

Aftermath

[edit]

The battle of Legnano put an end to Frederick Barbarossa's fifth descent in Italy and his attempt to hegemonize the municipalities of northern Italy.[158][11] Frederick also lost the military support of the German princes,[159] who, after the 10,000 knights provided at the beginning of his campaign and the 3,000 laboriously collected shortly before the battle of Legnano, would hardly have given Barbarossa more aid to resolve the situation in Italy, which would have brought them very little benefit.[159] Having no support at home, Frederick, to try to resolve the dispute, tried the diplomatic approach, with the armistice that was signed at the Venice congress of 1177.[158] In this agreement, the emperor recognized, among other things, Alexander III as a legitimate pontiff and submitted to papal power by recomposing the schism that had arisen some years before.[160][161] From then on, Beatrice I, Countess of Burgundy wife of Frederick ceased to be referred as Imperatrix ('empress') in the chancery productions, as her coronation as such had been made by an anti-pope and was thus declared nullified.[162]

The first negotiations for definitive peace took place in Piacenza between March and May 1183.[163] The Lombard League asked Frederick Barbarossa the complete autonomy of the cities, the possibility of the latter to freely erect walls and fortifications, the exemption from all types of taxes and the absence of any kind of interference by the emperor in local matters;[164] requests to which Frederick Barbarossa, in the first instance, firmly opposed.[165] Shortly before the negotiations in Piacenza, from an imperial perspective, however, an important event occurred: Alessandria submitted to the imperial power and was recognized by Frederick as a city of the Empire.[166]

The continuation of negotiations led to the signing of the Peace of Constance (25 June 1183),[159][167] which first of all provided for the recognition of the Lombard League by Frederick Barbarossa.[12] As regards the individual cities, the emperor made administrative, political and judicial concessions;[12] in particular, Frederick granted a wide autonomy with respect to the management of land resources such as forests, water and mills,[12] with respect to court cases and related penalties and, finally, with regard to military aspects, such as the recruitment of army and the free construction of defensive walls and castles.[46][168] As far as legal proceedings were concerned, the imperial vicars would have intervened in disputes only for the appeal cases that involved goods or compensation worth more than 25 lire, but applying the laws in force in the individual municipalities.[168] Moreover, Barbarossa confirmed the customary law that the cities had conquered in the thirty years of clashes with the Empire, and officially granted the municipalities the right to have a consul,[158] who had to swear allegiance to the emperor.[168]

The municipalities of the Lombard League, on the other hand, formally recognized the imperial authority and agreed to pay the fodro but not the royalties, which remained in the municipalities.[46][170] Furthermore, the Italian municipalities agreed to pay the Empire, as taxes, 15,000 one-off lire and an annual sum of 2,000 lire.[46] Earnings from the defeat of Frederick Barbarossa were not only Italian municipalities, but also the Papacy, which managed to emphasize its position of superiority over the Empire.[171] The peace of Constance was the only imperial recognition of the prerogatives of Italian municipalities: for this reason, it was celebrated for centuries.[172]

Alberto da Giussano and the Company of Death

[edit]The name of Alberto da Giussano appeared for the first time in the historical chronicle of the city of Milan written by the Dominican friar Galvano Fiamma in the first half of the 14th century, that is 150 years after the battle of Legnano.[173] Alberto da Giussano was described as a knight who distinguished himself, together with his brothers Ottone and Raniero, in the battle of 29 May 1176.[100] According to Galvano Fiamma, he headed the Company of Death,[173] a military association of 900 young knights.[174]

The Company of Death owed its name to the oath that made its members, which foresaw the struggle until the last breath without ever lowering its arms.[174] According to Galvano Fiamma, the Company of Death defended the Carroccio[175] to the extreme and then carried out, in the final stages of the battle of Legnano, a charge against the imperial army of Frederick Barbarossa.[176]

However, contemporary sources at the battle of Legnano do not mention either the existence of Alberto da Giussano or that of the Company of Death.[174] The stories of Fiamma should be taken with the benefit of the doubt since in his chronicles there are inaccuracies and legendary facts.[100]

National unification references

[edit]In a proclamation issued in Bergamo on 3 August 1848, the revolutionary leader Garibaldi referred to the historic battle of Legnano as a source of inspiration for his own struggle for the unification of Italy: "Bergamo will be the Pontida of the present generation, and God will bring us a Legnano!".[177] In a similar vein Il Canto degli Italiani, written in 1847 and now the Italian national anthem, contains the lines, "From the Alps to Sicily, Legnano is everywhere."

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ According to the Gesta Friderici of Godfrey of Viterbo[4]

- ^ According to the Gesta Friderici (of Godfrey of Viterbo) Frederick rode with 500 knights from Pavia to Como to join the new contingent, arriving via the Lukmanier pass, which numbered 2,000 knights according to the Annales Mediolanenses maiores of Sire Raul; To add are at least 500 Comaschi, who were either killed or captured(later mutilated) at the battle, according to the Gesta Friderici and the Continuatio Sanblasiana [1][4][5]

- ^ According to Percivaldi (The Lombardi who made the enterprise, p. 39), the term "arengo" derives from the terms Longobard herr (it. "Man") and ring (en. "circle"). However Giacomo Devoto (Etymological dictionary. Introduction to Italian etymology, Florence, Le Monnier 1968, p. 26) reports a different etymology: from gothic hari-hriggs, "army circle".

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Sire Raul, Annales Mediolanenses maiores, MGH SS. 18, 378

- ^ Annales Colonienses maximi. Cologne. 1238. p. 25b Anno Domini 1176, MG. SS rer. Germ, in us.schol., 128 f.

- ^ Peter N. Stearns and William Leonard Langer, The Encyclopedia of World History, 2001, p. 208

- ^ a b Godfrey of Viterbo, Gesta Friderici, MG. SS XXII, 329 V 982 ff.

- ^ Otto of Sankt Blasien, Continuatio Sanblasiana, SS. XX, 316

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Ars Bellica – Le grandi battaglie della storia – La battaglia di Legnano" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g D'Ilario 1984, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f g D'Ilario 1984, p. 23.

- ^ a b Percivaldi 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b "Alessandro III" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Federico I e i comuni" (in Italian). December 30, 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 155.

- ^ a b "Fratelli d'Italia" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 335.

- ^ "Festa della Lombardia" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 8.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 10.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 12.

- ^ a b Percivaldi 2009, p. 39.

- ^ Bordone & Sergi 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b Percivaldi 2009, p. 41.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 13.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. viii and 14.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 14.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 46.

- ^ a b D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f Federico I imperatore, detto il Barbarossa entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 55.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 15.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 59.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 61.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 16–22.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b c d e f Grillo 2010, p. 16.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 24.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 82.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d Percivaldi 2009, p. 198.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 118.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 24–30.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 28.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 124.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 129.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 38.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 145.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 39.

- ^ a b ALESSANDRO III entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 44.

- ^ a b Percivaldi 2009, p. 5.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 53–54.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 53–56.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, pp. 156–158.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 52.

- ^ Alessandria entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b Percivaldi 2009, p. 170.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 75.

- ^ a b D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 97.

- ^ a b D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 35.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 36.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d Grillo 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Gianazza 1975, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 125.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 102.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 157–161.

- ^ a b c d e f D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 76.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 120.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 89.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, pp. 9–10.

- ^ a b Agnoletto 1992, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Percivaldi 2009, p. 8.

- ^ Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b c d e f D'Ilario 1984, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 78.

- ^ a b c D'Ilario 1984, p. 233.

- ^ a b Autori vari 2015, p. 18.

- ^ Gianazza 1975, p. 12.

- ^ Soprintendenza 2014, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Agnoletto 1992, p. 38.

- ^ Soprintendenza 2014, p. 15.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 211–213.

- ^ a b D'Ilario 1984, p. 211.

- ^ Ferrarini & Stadiotti 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 120–121.

- ^ "La Flora" (PDF). Dovunque è Legnano - Periodico d'informazione sulla vita cittadina (in Italian). SpecialePalio: 15. Autumn 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 135.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b c d e f Grillo 2010, p. 145.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 141.

- ^ a b Gianazza 1975, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e Grillo 2010, p. 146.

- ^ a b c d e D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Gianazza 1975, p. 13.

- ^ Gianazza 1975, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 146–147.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 151.

- ^ Grillo 2010, pp. 151–152.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 234.

- ^ "Le testimonianze sulla chiesa di S.Martino ci riportano alla battaglia di Legnano" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Grillo 2010, p. 148.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 149.

- ^ a b D'Ilario 1984, p. 226.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 150.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 230.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 73.

- ^ a b D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 72.

- ^ Gesta Federici I imperatoris in Lombardia auctore cive Mediolanensi, ed. Oswald Holder-Egger, in 'Monumenta Germaniae Historica. Scriptores rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum' Hannover, Hahn 1892, p. 63.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. xiv.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 94.

- ^ Muratori 1868, p. 150.

- ^ Ferrario 1987, p. 11.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 104.

- ^ "Reti medioevali – Antologia delle fonti bassomedievali". Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 118.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 27.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 118–119.

- ^ D'Ilario 1984, p. 28.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 119.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 90.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 85.

- ^ a b c Agnoletto 1992, p. 39.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Le pubblicazioni de "Il Belvedere" – San Giorgio su Legnano – Cenni storici – Con il patrocinio dell'Amministrazione comunale (in Italian)

- ^ "Da leggenda a realtà: trovato il cunicolo del Castello". Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ a b c COSTANZA entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 165.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 171.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 191.

- ^ John B. Freed (2016), Frederick Barbarossa: The Prince and the Myth (Yale University Press).

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 153.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, pp. 153–154.

- ^ D'Ilario, Gianazza & Marinoni 1976, p. 154.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Percivaldi 2009, p. 197.

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 155.

- ^ Grillo 2010, p. 178.

- ^ Gianazza 1975, p. 16.

- ^ Cardini & Montesano 2006, p. 219.

- ^ a b Grillo 2010, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Grillo 2010, p. 153.

- ^ Alberto da Giussano entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ ALBERTO da Giussano entry (in Italian) in the Enciclopedia Treccani

- ^ Lucy Rial, "Garibaldi, Invention of a Hero", p. 74

References

[edit]- Agnoletto, Attilo (1992). San Giorgio su Legnano – storia, società, ambiente (in Italian). SBN IT\ICCU\CFI\0249761.

- Autori vari (2015). Il Palio di Legnano : Sagra del Carroccio e Palio delle Contrade nella storia e nella vita della città (in Italian).

- Autori vari (2014). Di città in città – Insediamenti, strade e vie d'acqua da Milano alla Svizzera lungo la Mediolanum-Verbannus (in Italian). Soprintendenza Archeologia della Lombardia.

- Bordone, Renato; Sergi, Giuseppe (2009). Dieci secoli di medioevo (in Italian). Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-16763-9.

- Cardini, Franco; Montesano, Marina (2006). Storia Medievale (in Italian). Le Monnier. ISBN 88-00-20474-0.

- D'Ilario, Giorgio; Gianazza, Egidio; Marinoni, Augusto (1976). Legnano e la battaglia (in Italian). Edizioni Landoni. SBN IT\ICCU\LO1\1256757.

- D'Ilario, Giorgio; Gianazza, Egidio; Marinoni, Augusto; Turri, Marco (1984). Profilo storico della città di Legnano (in Italian). Edizioni Landoni. SBN IT\ICCU\RAV\0221175.

- Ferrarini, Gabriella; Stadiotti, Marco (2001). Legnano. Una città, la sua storia, la sua anima (in Italian). Telesio editore. SBN IT\ICCU\RMR\0096536.

- Ferrario, Luigi (1987). Notizie storico statistiche (ristampa anastatica, Busto Arsizio, 1864) (in Italian). Atesa. SBN IT\ICCU\MIL\0017275.

- Gianazza, Egidio (1975). La battaglia di Legnano (in Italian). Atesa. SBN IT\ICCU\PUV\1179200.

- Grillo, Paolo (2010). Legnano 1176. Una battaglia per la libertà (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-9243-8.

- Muratori, Ludovico Antonio (1868). Annali d'Italia: dal principio dell'era volgare sino all'anno MDCCXLIX, Volume 4 (in Italian). Giachetti. SBN IT\ICCU\UMC\0098657.

- Percivaldi, Elena (2009). I Lombardi che fecero l'impresa. La Lega Lombarda e il Barbarossa tra storia e leggenda (in Italian). Ancora Editrice. ISBN 978-88-514-0647-9.

- Villari, Rosario (2000). Mille anni di storia (in Italian). Laterza. ISBN 88-420-6164-6.