Brainwashing

| Part of a series on |

| Behavioural influences |

|---|

| Fields of study |

| Topics |

Brainwashing[a] is the controversial theory that purports that the human mind can be altered or controlled against a person's will by manipulative psychological techniques.[1] Brainwashing is said to reduce its subject's ability to think critically or independently, to allow the introduction of new, unwanted thoughts and ideas into their minds,[2] as well as to change their attitudes, values, and beliefs.[3][4]

The term "brainwashing" was first used in English by Edward Hunter in 1950 to describe how the Chinese government appeared to make people cooperate with them during the Korean War. Research into the concept also looked at Nazi Germany and present-day North Korea, at some criminal cases in the United States, and at the actions of human traffickers.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the CIA's MKUltra experiments failed with no operational use of the subjects. Scientific and legal debate followed, as well as media attention, about the possibility of brainwashing being a factor when lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) was used,[5] or in the conversion of people to groups which are considered to be cults.[6]

Brainwashing has become a common theme in popular culture, especially in science fiction.[7] In casual speech, "brainwashing" and its verb form, "brainwash", are used figuratively to describe the use of propaganda to sway public opinion.[8]

China and the Korean War

[edit]The Chinese term xǐnǎo (traditional Chinese: 洗腦; simplified Chinese: 洗脑 lit. 'wash brain')[9] was originally used by early 20th century Chinese intellectuals to refer to modernizing one's way of thinking.[10] The term was later used to describe the coercive persuasion used under the Maoist government in China, which aimed to transform "reactionary" people into "right-thinking" members of the new Chinese social system.[11] The term punned on the Taoist custom of "cleansing/washing the heart/mind" (Chinese: 洗心; pinyin: xǐxīn) before conducting ceremonies or entering holy places.[b]

The earliest known English-language usage of the word "brainwashing" in an article by a journalist Edward Hunter, in Miami News, published in 1950.[12] Hunter was an anticommunist and was alleged to be a CIA agent working undercover.[13] Hunter and others used the Chinese term to explain why, during the Korean War (1950–1953), some American prisoners of war (POWs) cooperated with their Chinese captors, and even in a few cases defected to their side.[14] British radio operator Robert W. Ford[15][16] and British army Colonel James Carne also claimed that the Chinese subjected them to brainwashing techniques during their imprisonment.[17]

The U.S. military and government laid charges of brainwashing in an effort to undermine confessions made by POWs to war crimes, including biological warfare.[18] After Chinese radio broadcasts claimed to quote Frank Schwable, Chief of Staff of the First Marine Air Wing admitting to participating in germ warfare, United Nations commander General Mark W. Clark asserted: "Whether these statements ever passed the lips of these unfortunate men is doubtful. If they did, however, too familiar are the mind-annihilating methods of these Communists in extorting whatever words they want ... The men themselves are not to blame, and they have my deepest sympathy for having been used in this abominable way."[19]

Beginning in 1953, Robert Jay Lifton interviewed American servicemen who had been POWs during the Korean War as well as priests, students, and teachers who had been held in prison in China after 1951. In addition to interviews with 25 Americans and Europeans, Lifton interviewed 15 Chinese citizens who had fled after having been subjected to indoctrination in Chinese universities. (Lifton's 1961 book Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of "Brainwashing" in China, was based on this research.)[20] Lifton found that when the POWs returned to the United States their thinking soon returned to normal, contrary to the popular image of "brainwashing."[21]

In 1956, after reexamining the concept of brainwashing following the Korean War, the U.S. Army published a report entitled Communist Interrogation, Indoctrination, and Exploitation of Prisoners of War, which called brainwashing a "popular misconception". The report concludes that "exhaustive research of several government agencies failed to reveal even one conclusively documented case of 'brainwashing' of an American prisoner of war in Korea."[22]

Legal cases and the "brainwashing defense"

[edit]

The concept of brainwashing has been raised in defense of criminal charges. The 1969 to 1971 case of Charles Manson, who was said to have brainwashed his followers to commit murder and other crimes, brought the issue to renewed public attention.[24][25]

In 1974, Patty Hearst, a member of the wealthy Hearst family, was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a left-wing militant organization. After several weeks of captivity, she agreed to join the group and took part in their activities. In 1975, she was arrested and charged with bank robbery and the use of a gun in committing a felony. Her attorney, F. Lee Bailey, argued in her trial that she should not be held responsible for her actions since her treatment by her captors was the equivalent of the alleged brainwashing of Korean War POWs (see also Diminished responsibility).[26] Bailey developed his case in conjunction with psychiatrist Louis Jolyon West and psychologist Margaret Singer. They had both studied the experiences of Korean War POWs. (In 1996, Singer published her theories in her best-selling book Cults in Our Midst.[27][28][29]) Despite this defense, Hearst was found guilty.[26]

In 1990, Steven Fishman, who was a member of the Church of Scientology, was charged with mail fraud for conducting a scheme to sue large corporations via conspiring with minority stockholders in shareholder class action lawsuits. Fishman's attorneys notified the court that they intended to rely on an insanity defense, using the theories of brainwashing and the expert witnesses of Singer and Richard Ofshe to claim that the Church of Scientology had practiced brainwashing on him, which left him unsuitable to make independent decisions.

The court ruled that the use of brainwashing theories is inadmissible in expert witnesses, citing the Frye standard, which states that scientific theories utilized by expert witnesses must be generally accepted in their respective fields.[30] Since then, United States courts have consistently rejected testimony about mind control or brainwashing on the grounds that these theories are not part of accepted science under the Frye standard.[31]

In 2003, the brainwashing defense was used unsuccessfully in defense of Lee Boyd Malvo, who was charged with murder for his part in the D.C. sniper attacks.[32][33] Allegations of brainwashing have also been raised by plaintiffs in child custody cases.[34][35]

Thomas Andrew Green, in his 2014 book Freedom and Criminal Responsibility in American Legal Thought, argues that the brainwashing defense undermines the law's fundamental premise of free will.[36][37] In 2003, forensic psychologist Dick Anthony said that "no reasonable person would question that there are situations where people can be influenced against their best interests, but those arguments are evaluated based on fact, not bogus expert testimony."[33]

Anti-cult movement

[edit]

In the 1970s and 1980s, the anti-cult movement applied the concept of brainwashing to explain seemingly sudden and dramatic religious conversions to some new religious movements (NRMs) and other groups that they considered cults.[38][39] News media reports tended to accept their view[40] and social scientists sympathetic to the anti-cult movement, who were usually psychologists, developed revised models of mind control.[38] While some psychologists were receptive to the concept, sociologists were, for the most part, skeptical of its ability to explain conversion.[41] Critics of Mormonism have accused it of brainwashing its adherents.[42]

Philip Zimbardo defined mind control as "the process by which individual or collective freedom of choice and action is compromised by agents or agencies that modify or distort perception, motivation, affect, cognition or behavioral outcomes,"[43] and he suggested that any human being is susceptible to such manipulation.[44]

Benjamin Zablocki, late professor of sociology at Rutgers university said that the number of people who attest to brainwashing in interviews (performed in accordance with guidelines of the National Institute of Mental Health and National Science Foundation) is too large to result from anything other than a genuine phenomenon.[45] He said that in the two most prestigious journals dedicated to the sociology of religion there have been no articles "supporting the brainwashing perspective," while over one hundred such articles have been published in other journals "marginal to the field."[46] He concluded that the concept of brainwashing had been blacklisted.[47][46][48]

Eileen Barker criticized the concept of mind control because it functioned to justify costly interventions such as deprogramming or exit counseling.[49] She has also criticized some mental health professionals, including Singer, for accepting expert witness jobs in court cases involving NRMs.[50] Barker's 1984 book, The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing?,[51] describes the religious conversion process to the Unification Church (whose members are sometimes informally referred to as Moonies), which had been one of the best-known groups said to practice brainwashing.[52][53] Barker spent close to seven years studying Unification Church members and wrote that she rejects the "brainwashing" theory because it does not explain why many people attended a recruitment meeting and did not become members nor why so many members voluntarily disaffiliate or leave groups.[49][54][55][56][57]

James Richardson said that if the new religious movements had access to powerful brainwashing techniques, one would expect that they would have high growth rates, yet in fact, most have not had notable success in recruiting or retaining members.[58] For this and other reasons, sociologists of religion including David Bromley and Anson Shupe consider the idea that "cults" are brainwashing American youth to be "implausible."[59]

Thomas Robbins, Massimo Introvigne, Lorne Dawson, Gordon Melton, Marc Galanter, and Saul Levine, amongst other scholars researching NRMs, have argued and established to the satisfaction of courts, relevant professional associations and scientific communities that there exists no generally accepted scientific theory, based upon methodologically sound research, that supports the concept of brainwashing.[60]

In 1999, forensic psychologist Dick Anthony criticized another adherent to this view, Jean-Marie Abgrall, for allegedly employing a pseudoscientific approach and lacking any evidence that anyone's worldview was substantially changed by these coercive methods. He claimed that the concept and the fear surrounding it was used as a tool for the anti-cult movement to rationalize the persecution of minority religious groups.[61] Additionally, Anthony, in the book Misunderstanding Cults, argues that the term "brainwashing" has such sensationalist connotations that its use is detrimental to any further scientific inquiry.[62]

In 2016, Israeli anthropologist of religion and fellow at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute Adam Klin-Oron said about then proposed "anti-cult" legislation:

In the 1980s there was a wave of 'brainwashing' claims, and then parliaments around the world examined the issue, courts around the world examined the issue, and reached a clear ruling: That there is no such thing as cults…that the people making these claims are often not experts on the issue. And in the end courts, including in Israel, rejected expert witnesses who claimed there is "brainwashing."[63]

Scientific research

[edit]

Research by the U.S. government

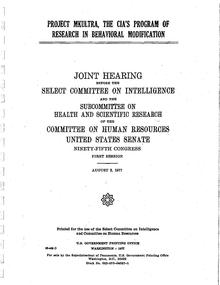

[edit]For 20 years, starting in the early 1950s, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the U.S. Department of Defense conducted secret research, including Project MKUltra, in an attempt to develop practical brainwashing techniques; These experiments ranged "from electroshock to high doses of LSD".[64]

The director Sidney Gottlieb and his team were apparently able to "blast away the existing mind" of a human being by using torture techniques;[64] however, reprogramming, in terms of finding "a way to insert a new mind into that resulting void",[64] was not so successful.[65][66]

Controversial psychiatrist Colin A. Ross claims that the CIA was successful in creating programmable so-called "Manchurian Candidates" even at the time.[67] The CIA experiments using various psychedelic drugs such as LSD and Mescaline drew from previous Nazi human experimentation.[68]

In 1979, John D. Marks wrote in his book The Search for the Manchurian Candidate that until the MKUltra program was effectively terminated in 1963, the agency's researchers had found no reliable way to brainwash another person, as all experiments at some stage always ended in either amnesia or catatonia, making any operational use impossible.[13]

A bipartisan Senate Armed Services Committee report, released in part in December 2008 and in full in April 2009, reported that U.S. military trainers who came to Guantánamo Bay in December 2002 had based an interrogation class on a chart copied from a 1957 Air Force study of "Chinese Communist" brainwashing techniques used to elicit false confessions from American POWs during the Korean War. The report showed how the Secretary of Defense's 2002 authorization of the aggressive techniques at Guantánamo led to their use in Afghanistan and in Iraq, including at Abu Ghraib.[69]

American Psychological Association Task Force

[edit]In 1983, the American Psychological Association (APA) asked Singer to chair a task force called the APA Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Techniques of Persuasion and Control (DIMPAC) to investigate whether brainwashing or coercive persuasion did indeed control cults members. The Task Force concluded that:[70]

Cults and large group awareness trainings have generated considerable controversy because of their widespread use of deceptive and indirect techniques of persuasion and control. These techniques can compromise individual freedom, and their use has resulted in serious harm to thousands of individuals and families. This report reviews the literature on this subject, proposes a new way of conceptualizing influence techniques, explores the ethical ramifications of deceptive and indirect techniques of persuasion and control, and makes recommendations addressing the problems described in the report.

On 11 May 1987, the APA's Board of Social and Ethical Responsibility for Psychology (BSERP) rejected the DIMPAC report because the report "lacks the scientific rigor and evenhanded critical approach necessary for APA imprimatur" and concluded that "after much consideration, BSERP does not believe that we have sufficient information available to guide us in taking a position on this issue."[71]

Other areas and studies

[edit]

Joost Meerloo, a Dutch psychiatrist, was an early proponent of the concept of brainwashing. "Menticide" is a neologism he coined meaning "killing of the mind". Meerloo's view was influenced by his experiences during the German occupation of his country during the Second World War and his work with the Dutch government and the American military in the interrogation of accused Nazi war criminals. He later emigrated to the United States and taught at Columbia University.[72] His best-selling 1956 book, The Rape of the Mind, concludes by saying:

The modern techniques of brainwashing and menticide—those perversions of psychology—can bring almost any man into submission and surrender. Many of the victims of thought control, brainwashing, and menticide that we have talked about were strong men whose minds and wills were broken and degraded. But although the totalitarians use their knowledge of the mind for vicious and unscrupulous purposes, our democratic society can and must use its knowledge to help man to grow, to guard his freedom, and to understand himself.[73]

Russian historian Daniel Romanovsky, who interviewed survivors and eyewitnesses in the 1970s, reported on what he called "Nazi brainwashing" of the people of Belarus by the occupying Germans during the Second World War, which took place through both mass propaganda and intense re-education, especially in schools. Romanovsky noted that very soon, most people had adopted the Nazi view that the Jews were an inferior race and were closely tied to the Soviet government, views that had not been at all common before the German occupation.[74][75][76][77][78][79]

Italy has had controversy over the concept of plagio, a crime consisting in an absolute psychological—and eventually physical—domination of a person. The effect is said to be the annihilation of the subject's freedom and self-determination and the consequent negation of his or her personality. The crime of plagio has rarely been prosecuted in Italy, and only one person was ever convicted. In 1981, an Italian court found that the concept is imprecise, lacks coherence and is liable to arbitrary application.[80]

Recent scientific book publications in the field of the mental disorder "dissociative identity disorder" (DID) mention torture-based brainwashing by criminal networks and malevolent actors as a deliberate means to create multiple "programmable" personalities in a person to exploit this individual for sexual and financial reasons.[81][82][83][84][85] Earlier scientific debates in the 1980s and 1990s about torture-based ritual abuse in cults was known as "satanic ritual abuse," which was mainly viewed as a "moral panic."[86]

Brain-Washing: A Synthesis of the Russian Textbook on Psychopolitics published by the Church of Scientology in 1955 about brainwashing. L. Ron Hubbard authored the text and alleged it was the secret manual written by Lavrentiy Beria, the Soviet secret police chief, in 1936.[87] When the FBI ignored him, Hubbard wrote again stating that Soviet agents had, on three occasions, attempted to hire him to work against the United States, and were upset about his refusal,[88] and that one agent specifically attacked him using electroshock as a weapon.[89]

Kathleen Barry, co-founder of the United Nations NGO, the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women (CATW),[90][91] prompted international awareness of human sex trafficking in her 1979 book Female Sexual Slavery.[92] In his 1986 book Woman Abuse: Facts Replacing Myths, Lewis Okun reported that: "Kathleen Barry shows in Female Sexual Slavery that forced female prostitution involves coercive control practices very similar to thought reform."[93] In their 1996 book, Casting Stones: Prostitution and Liberation in Asia and the United States, Rita Nakashima Brock and Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite report that the methods commonly used by pimps to control their victims "closely resemble the brainwashing techniques of terrorists and paranoid cults."[94]

In his 2000 book, Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism, Robert Lifton applied his original ideas about thought reform to Aum Shinrikyo and the War on Terrorism, concluding that, in this context, thought reform was possible without violence or physical coercion. He also pointed out that in their efforts against terrorism, Western governments were also using some alleged mind control techniques.[95]

In her 2004 popular science book, Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control, neuroscientist and physiologist Kathleen Taylor reviewed the history of mind control theories, as well as notable incidents. In it, she theorized that persons under the influence of brainwashing may have more rigid neurological pathways, and that can make it more difficult to rethink situations or to be able to later reorganize these pathways.[96][97]

In 2006 Brainwash: The Secret History of Mind Control (ISBN 0-340-83161-8) is a non-fiction book published by Hodder & Stoughton about the evolution of brainwashing from its origins in the Cold War through to today's War on Terror.[98][99][100] The author, Dominic Streatfeild, uses formerly classified documentation and interviews from the CIA.[101]

In popular culture

[edit]

In George Orwell's 1949 dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four, the main character is subjected to imprisonment, isolation, and torture to conform his thoughts and emotions to the wishes of the rulers of the book's fictional future totalitarian society. The torturer, representing the authorities, says to that character, "we make the brain perfect before we blow it out...Everyone is washed clean."[102] Orwell's vision influenced Hunter and is still reflected in the popular concept of brainwashing.[103][104]

In the 1950s, some American films were made that featured brainwashing of POWs, including The Rack, The Bamboo Prison, Toward the Unknown, and The Fearmakers. Forbidden Area told the story of Soviet secret agents who had been brainwashed through classical conditioning by their own government so they wouldn't reveal their identities. In 1962, The Manchurian Candidate (based on the 1959 novel by Richard Condon) "put brainwashing front and center" by featuring a plot by the Soviet government to take over the United States by using a brainwashed sleeper agent for political assassination.[105][106][107]

The concept of brainwashing became popularly associated with the research of Russian psychologist Ivan Pavlov, which mostly involved dogs as subjects.[108] In The Manchurian Candidate, the head brainwasher is "Dr. Yen Lo, of the Pavlov Institute."[109]

The science fiction stories of Cordwainer Smith (pen name of Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger (1913–1966), a U.S. Army officer who specialized in military intelligence and psychological warfare during the Second World War and the Korean War) depict brainwashing to remove memories of traumatic events as a normal and benign part of future medical practice.[110]

Brainwashing remains an important theme in science fiction. A subgenre is corporate mind control, in which a future society is run by one or more business corporations that dominate society, using advertising and mass media to control the population's thoughts and feelings.[111] Terry O'Brien commented: "Mind control is such a powerful image that if hypnotism did not exist, then something similar would have to have been invented: The plot device is too useful for any writer to ignore. The fear of mind control is equally as powerful an image."[112]

See also

[edit]- Behavior modification

- Indoctrination

- Orwellian

- Manipulation (psychology)

- Abusive power and control

- Psychological warfare

- Hypnosis

- Political abuse of psychiatry

- Reality distortion field

- Science fiction

- Coercion

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

- Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism

- Mind control in popular culture

Further reading

[edit]- Lifton, Robert J. (1961). Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism: A Study of "Brainwashing" in China. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-8078-4253-9.; Reprinted, with a new preface: University of North Carolina Press, 1989 (Online at Internet Archive).

- Lifton, Robert J. (2000). Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism. Owl Books.

- Meerloo, Joost (1956). "The Rape of the Mind: The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide, and Brainwashing". World Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- Taylor, Kathleen (2004). Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control. Oxford University Press.

- Zablocki, B. (1997). "The Blacklisting of a Concept. The Strange History of the Brainwashing Conjecture in the Sociology of Religion". Nova Religio. 1 (1): 96–121. doi:10.1525/nr.1997.1.1.96.

- Zablocki, B (1998). "Exit Cost Analysis: A New Approach to the Scientific Study of Brainwashing". Nova Religio. 2 (1): 216–249. doi:10.1525/nr.1998.1.2.216.

- Zimbardo, P. (1 November 2002). "Mind Control: Psychological Reality or Mindless Rhetoric?". Monitor on Psychology. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education.

- ^ xīn can mean "heart", "mind", or "centre" depending on context. For example, xīn zàng bìng [zh] means Cardiovascular disease, but xīn lǐ yī shēng [zh] means psychologist, and shì zhōng xīn [zh] means Central business district.

References

[edit]- ^ "Brainwashing | Cults, Indoctrination, Manipulation | Britannica".

- ^ Campbell, Robert Jean (2004). Campbell's Psychiatric Dictionary. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 403.

- ^ Corsini, Raymond J. (2002). The Dictionary of Psychology. Psychology Press. p. 127.

- ^ Kowal, D.M. (2000). "Brainwashing". In Love, A.E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Psychology. Vol. 1. American Psychological Association. pp. 463–464. doi:10.1037/10516-173. ISBN 1-55798-650-9.

- ^ Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Religion. Vol. 2. Gyan Publishing House. 2005.

- ^ Wright, Stuart (December 1997). "Media coverage of unconventional religion: Any "good news" for minority faiths?". Review of Religious Research. 39 (2): 101–115. doi:10.2307/3512176. JSTOR 3512176.

- ^ O'Brien, Terry (2005). Westfahl, Gary (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Brainwash Definition & Meaning". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 22 July 2023. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Word dictionary – 洗腦 – MDBG English to Chinese dictionary". mdbg.net. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- ^ Mitchell, Ryan (July–September 2019). "China and the Political Myth of 'Brainwashing". Made in China Journal. 3. Archived from the original on 1 June 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Kathleen (2006). Brainwashing: The Science of Thought Control. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0199204786. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Crean, Jeffrey (2024). The Fear of Chinese Power: an International History. New Approaches to International History series. London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-350-23394-2.

- ^ a b Marks, John (1979). "Chapter 8. Brainwashing". The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and mind control. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0812907735. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

In September 1950, the Miami News published an article by Edward Hunter titled '"Brain-Washing" Tactics Force Chinese into Ranks of Communist Party'. It was the first printed use in any language of the term "brainwashing", Hunter, a CIA propaganda operator who worked undercover as a journalist, turned out a steady stream of books and articles on the subject.

- ^ Browning, Michael (14 March 2003). "Was kidnapped Utah teen brainwashed?". Palm Beach Post. Palm Beach. ISSN 1528-5758.

During the Korean War, captured American soldiers were subjected to prolonged interrogations and harangues by their captors, who often worked in relays and used the "good-cop, bad-cop" approach – alternating a brutal interrogator with a gentle one. It was all part of "Xi Nao" (washing the brain). The Chinese and Koreans were making valiant attempts to convert the captives to the communist way of thought.

- ^ Ford, R.C. (1990). Captured in Tibet. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195815702.

- ^ Ford, R.C. (1997). Wind between the Worlds: Captured in Tibet. SLG Books. ISBN 978-0961706692.

- ^ "Red germ charges cite 2 U.S. Marines" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 February 1954. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Endicott, Stephen; Hagerman, Edward (1998). The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the early Cold War. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253334725.

- ^ "Clark denounces germ war charges" (PDF). The New York Times. 24 February 1953. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- ^ Wilkes, A.L. (1998). Knowledge in Minds. Psychology Press. p. 323. ISBN 978-0863774393.

- ^ Lifton, Robert J. (April 1954). "Home by Ship: Reaction patterns of American prisoners of war repatriated from North Korea". American Journal of Psychiatry. 110 (10): 732–739. doi:10.1176/ajp.110.10.732. PMID 13138750.

- ^ U.S. Department of the Army (15 May 1956). Communist Interrogation, Indoctrination, and Exploitation of Prisoners of War (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 17, 51. Pamphlet number 30-101. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ Lucas, Dean (14 May 2013). "Patty Hearst". Famous Pictures Magazine. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Minds on Trial: Great Cases in Law and Psychology, by Charles Patrick Ewing, Joseph T. McCann pp. 34–36

- ^ Shifting the Blame: How Victimization Became a Criminal Defense, Saundra Davis Westervelt, Rutgers University Press, 1998. p. 158

- ^ a b Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, James T. Richardson, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012, p. 518 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Cults in Our Midst: The Continuing Fight Against Their Hidden Menace Archived 2 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Margaret Thaler Singer, Jossey-Bass, publisher, 2003, ISBN 0787967416

- ^ Clarke, Peter; Clarke, Reader in Modern History Fellow Peter (2004). Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134499700.

- ^ Hilts, Philip J. (9 January 1999). "Louis J. West, 74, Psychiatrist Who Studied Extremes, Dies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "United States v. Fishman (1990)". Justia Law. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Anthony, Dick; Robbins, Thomas (1992). "Law, social science and the 'brainwashing' exception to the first amendment". Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 10 (1): 5–29. doi:10.1002/bsl.2370100103. Archived from the original on 13 March 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2023.

- ^ Mental Condition Defences and the Criminal Justice System: Perspectives from Law and Medicine, Ben Livings, Alan Reed, Nicola Wake, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015, p. 98 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Oldenburg, Don (2003-11-21). "Stressed to Kill: The Defense of Brainwashing; Sniper Suspect's Claim Triggers More Debate" Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post, reproduced in Defence Brief, issue 269, published by Steven Skurka & Associates

- ^ Warshak, R. A. (2010). Divorce Poison: How to Protect Your Family from Bad-mouthing and Brainwashing. New York: Harper Collins.

- ^ Richardson, James T. Regulating Religion: Case Studies from Around the Globe, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers 2004, p. 16, ISBN 978-0306478871.

- ^ Freedom and Criminal Responsibility in American Legal Thought, Thomas Andrew Green, Cambridge University Press, 2014, p. 391 [ISBN missing]

- ^ LaFave's Criminal Law, 5th (Hornbook Series), Wayne LaFave, West Academic, 18 March 2010, pp. 208–210 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Bromley, David G. (1998). "Brainwashing". In William H. Swatos Jr. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Society. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-7619-8956-1.

- ^ Barker, Eileen: New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1989.

- ^ Wright, Stewart A. (1997). "Media Coverage of Unconventional Religion: Any 'Good News' for Minority Faiths?". Review of Religious Research. 39 (2): 101–115. doi:10.2307/3512176. JSTOR 3512176.

- ^ Barker, Eileen (1986). "Religious Movements: Cult and Anti-Cult Since Jonestown". Annual Review of Sociology. 12: 329–346. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.001553.

- ^ Helfrich, R. (2021). Mormon Studies: A Critical History. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4766-4511-7. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ^ Zimbardo, Philip G. (November 2002). "Mind Control: Psychological Reality or Mindless Rhetoric?". Monitor on Psychology. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

Mind control is the process by which individual or collective freedom of choice and action is compromised by agents or agencies that modify or distort perception, motivation, affect, cognition or behavioral outcomes. It is neither magical nor mystical, but a process that involves a set of basic social psychological principles. Conformity, compliance, persuasion, dissonance, reactance, guilt and fear arousal, modeling, and identification are some of the staple social influence ingredients well-studied in psychological experiments and field studies. In some combinations, they create a powerful crucible of extreme mental and behavioral manipulation when synthesized with several other real-world factors, such as charismatic, authoritarian leaders, dominant ideologies, social isolation, physical debilitation, induced phobias, and extreme threats or promised rewards that are typically deceptively orchestrated, over an extended time period in settings where they are applied intensively. A body of social science evidence shows that when systematically practiced by state-sanctioned police, military or destructive cults, mind control can induce false confessions, create converts who willingly torture or kill 'invented enemies,' and engage indoctrinated members to work tirelessly, give up their money—and even their lives—for 'the cause.'

- ^ Zimbardo, P (1997). "What messages are behind today's cults?". Monitor on Psychology: 14. Archived from the original on 2 May 1998. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ Zablocki, Benjamin (2001). Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field. U of Toronto Press. pp. 194–201. ISBN 978-0-8020-8188-9.

- ^ a b Zablocki, Benjamin. (April 1998). "TReply to Bromley". Nova Religio. 1 (2): 267–271. doi:10.1525/nr.1998.1.2.267.

- ^ Zablocki, Benjamin. (October 1997). "The Blacklisting of a Concept: The Strange History of the Brainwashing Conjecture in the Sociology of Religion". Nova Religio. 1 (1): 96–121. doi:10.1525/nr.1997.1.1.96.

- ^ Phil Zuckerman. Invitation to the Sociology of Religion. Psychology Press, 24 July 2003 p. 28 [ISBN missing]

- ^ a b Review, William Rusher, National Review, 19 December 1986.

- ^ Barker, Eileen (1995). "The Scientific Study of Religion? You Must Be Joking!". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 34 (3): 287–310. doi:10.2307/1386880. JSTOR 1386880.

- ^ Eileen Barker, The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing?, Blackwell Publishers, Oxford, United Kingdom, ISBN 0-631-13246-5.

- ^ Moon's death marks end of an era Archived 29 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Eileen Barker, CNN, 3 September 2012, Although Moon is likely to be remembered for all these things—mass weddings, accusations of brainwashing, political intrigue and enormous wealth—he should also be remembered as creating what was arguably one of the most comprehensive and innovative theologies embraced by a new religion of the period.

- ^ Hyung-Jin Kim (2 September 2012). "Unification Church founder Rev. Sun Myung Moon dies at 92". USA Today. ISSN 0734-7456. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

The Rev. Sun Myung Moon was a self-proclaimed messiah who built a global business empire. He called both North Korean leaders and American presidents his friends but spent time in prisons in both countries. His followers around the world cherished him, while his detractors accused him of brainwashing recruits and extracting money from worshippers.

- ^ New Religious Movements – Some Problems of Definition George Chryssides, Diskus, 1997.

- ^ The Market for Martyrs Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Laurence Iannaccone, George Mason University, 2006, "One of the most comprehensive and influential studies was The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing? by Eileen Barker (1984). Barker could find no evidence that Moonie recruits were ever kidnapped, confined, or coerced. Participants at Moonie retreats were not deprived of sleep; the lectures were not "trance-inducing" and there was not much chanting, no drugs or alcohol, and little that could be termed a "frenzy" or "ecstatic" experience. People were free to leave, and leave they did. Barker's extensive enumerations showed that among the recruits who went so far as to attend two-day retreats (claimed to beMoonie's most effective means of "brainwashing"), fewer than 25% joined the group for more than a week, and only 5% remained full-time members one year later. And, of course, most contacts dropped out before attending a retreat. Of all those who visited a Moonie center at least once, not one in two hundred remained in the movement two years later. With failure rates exceeding 99.5%, it comes as no surprise that full-time Moonie membership in the U.S. never exceeded a few thousand. And this was one of the most successful New Religious Movements of the era!"

- ^ Oakes, Len "By far the best study of the conversion process is Eileen Barker's The Making of a Moonie [...]" from Prophetic Charisma: The Psychology of Revolutionary Religious Personalities, 1997, ISBN 0-8156-0398-3

- ^ Storr, Anthony (1996). Feet of clay: a study of gurus. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83495-2.

- ^ Richardson, James T. (June 1985). "The active vs. passive convert: paradigm conflict in conversion/recruitment research". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 24 (2): 163–179. doi:10.2307/1386340. JSTOR 1386340.

- ^ "Brainwashing by Religious Cults". religioustolerance.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2004.

- ^ Richardson, James T. 2009. "Religion and The Law" in The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Religion. Peter Clarke. (ed) Oxford Handbooks Online. p. 426

- ^ Anthony, Dick (1999). "Pseudoscience and Minority Religions: An Evaluation of the Brainwashing Theories of Jean-Marie Abgrall". Social Justice Research. 12 (4): 421–456. doi:10.1023/A:1022081411463. S2CID 140454555.

- ^ Zablocki, Benjamin; Robbins, Thomas, eds. (2001). "Introduction: Finding a Middle Ground in a Polarized Scholarly Arena". Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field. University of Toronto Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8020-8188-9.

- ^ [1] Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Israel

- ^ a b c "The CIA's Secret Quest for Mind Control: Torture, LSD and A 'Poisoner in Chief'". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Anthony, Dick (1999). "Pseudoscience and Minority Religions: An evaluation of the brainwashing theories of Jean-Marie". Social Justice Research. 12 (4): 421–456. doi:10.1023/A:1022081411463. S2CID 140454555.

- ^ "Chapter 3, part 4: Supreme Court Dissents Invoke the Nuremberg Code: CIA and DOD Human Subjects Research Scandals". Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments Final Report. Archived from the original on 9 November 2004. Retrieved 24 August 2005. "MKUltra, began in 1950 and was motivated largely in response to alleged Soviet, Chinese, and North Korean uses of mind-control techniques on U.S. prisoners of war in Korea."

- ^ "Book Review". Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2 (3): 123–128. 2001. doi:10.1300/J229v02n03_08. S2CID 220439052.

- ^ The Search for the Manchurian Candidate: The CIA and Mind Control: By John Marks. P 93 (c)1979 by John Marks Published by Times Books ISBN 0-8129-0773-6

- ^ Chaddock, Gail Russell (22 April 2009). "Report says top officials set tone for detainee abuse". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 4 January 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Singer, Margaret; Goldstein, Harold; Langone, Michael; Miller, Jesse S.; Temerlin, Maurice K.; West, Louis J. (November 1986). Report of the APA Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Techniques of Persuasion and Control (Report). Archived from the original on 4 January 2023. Retrieved 4 January 2023 – via Baylor University.

- ^ American Psychological Association Board of Social and Ethical Responsibility for Psychology (BSERP) (11 May 1987). "APA Memorandum to Members of the Task Force on DIMPAC". Archived from the original on 11 March 2000. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

BSERP thanks the Task Force on Deceptive and Indirect Methods of Persuasion and Control for its service but is unable to accept the report of the Task Force. In general, the report lacks the scientific rigor and evenhanded critical approach necessary for APA imprimatur.

- ^ The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies, Jonathan Auerbach, Russ Castronovo, Oxford University Press, 2014, p. 114 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Meerloo, Joost (1956). "The Rape of the Mind: The Psychology of Thought Control, Menticide, and Brainwashing". World Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ^ Nazi Europe and the Final Solution, David Bankier, Israel Gutman, Berghahn Books, 2009, pp. 282–285.

- ^ Gray Zones: Ambiguity and Compromise in the Holocaust and its Aftermath, Jonathan Petropoulos, John Roth, Berghahn Books, 2005, p. 209 [ISBN missing]

- ^ The Minsk Ghetto 1941–1943: Jewish Resistance and Soviet Internationalism, Barbara Epstein, University of California Press, 2008, p. 295 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Bringing the Dark Past to Light: The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe, John-Paul Himka, Joanna Beata Michlic, University of Nebraska Press, 2013, pp. 74, 78 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "Interview". Angelfire.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ *Romanovsky, Daniel (2009), "The Soviet Person as a Bystander of the Holocaust: The case of eastern Belorussia", in Bankier, David; Gutman, Israel (eds.), Nazi Europe and the Final Solution, Berghahn Books, p. 276, ISBN 978-1845454104

- Romanovsky, D. (1999). "The Holocaust in the Eyes of Homo Sovieticus: A Survey Based on Northeastern Belorussia and Northwestern Russia". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 13 (3): 355–382. doi:10.1093/hgs/13.3.355.

- Romanovsky, Daniel (1997), "Soviet Jews Under Nazi Occupation in Northeastern Belarus and Western Russia", in Gitelman, Zvi (ed.), Bitter Legacy: Confronting the Holocaust in the USSR, Indiana University Press, p. 241

- ^ Alessandro Usai Profili penali dei condizionamenti mentali, Milano, 1996 ISBN 88-14-06071-1. [page needed]

- ^ Schwartz, Rachel Wingfield (22 March 2018), "'An evil cradling?' Cult practices and the manipulation of attachment needs in ritual abuse", Ritual Abuse and Mind Control, Routledge, pp. 39–55, doi:10.4324/9780429479700-2, ISBN 978-0-429-47970-0, retrieved 11 July 2021

- ^ Miller, Alison (11 May 2018), "Becoming Yourself", Becoming Yourself: Overcoming Mind Control and Ritual Abuse, Routledge, pp. 347–370, doi:10.4324/9780429472251-21, ISBN 978-0-429-47225-1, retrieved 25 May 2023

- ^ Miller, Alison (8 May 2018). Healing the Unimaginable. doi:10.4324/9780429475467. ISBN 978-0429475467.

- ^ Alayarian, A. (2018). Trauma, Torture and Dissociation: A Psychoanalytic View. (n.p.): Taylor & Francis. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Schwartz, H. L. (2013). The Alchemy of Wolves and Sheep: A Relational Approach to Internalized Perpetration in Complex Trauma Survivors. US: Taylor & Francis. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Goode, Erich; Ben-Yehuda, Nachman (1994). "Moral Panics: Culture, Politics, and Social Construction". Annual Review of Sociology. 20: 149–171. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.20.080194.001053. ISSN 0360-0572. JSTOR 2083363. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ Paul F. Boller (1989). They Never Said It : A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, and Misleading Attributions. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-505541-2.

brain washing hubbard 1936.

- ^ Atack, Jon (1990). A Piece of Blue Sky: Scientology, Dianetics and L. Ron Hubbard Exposed. Lyle Stuart Books. p. 140. ISBN 081840499X. OL 9429654M.

- ^ California (State). California. Court of Appeal (2nd Appellate District). Records and Briefs. p. 33.

- ^ "A Distinctive Style Article". Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ "On the Issues Article". Ontheissuesmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ Biography at The People Speak Radio Archived 15 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Woman Abuse: Facts Replacing Myths, Lewis Okun, SUNY Press, 1986, p. 133

- ^ Casting Stones: Prostitution and Liberation in Asia and the United States, Rita Nakashima Brock, Susan Brooks Thistlethwaite, Fortress Press, 1996, p. 166

- ^ Destroying the World to Save It: Aum Shinrikyo, Apocalyptic Violence, and the New Global Terrorism, Owl Books, 2000. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Szimhart, Joseph (July–August 2005). "Thoughts on thought control". Skeptical Inquirer. 29 (4): 56–57.

- ^ Hawkes, Nigel (27 November 2004). "Brainwashing by Kathleen Taylor". The Times. London: Times Newspapers Ltd. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "TLS - Times Literary Supplement". Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ "Et cetera: Sep 23". TheGuardian.com. 23 September 2006.

- ^ Delaney, Tim (2007). "Brainwash: The Secret History of Mind Control". Library Journal. 132 (4): 95. ISSN 0363-0277.

- ^ The Intelligence Officer's Bookshelf

- ^ Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. ISBN 978-0451524935.

- ^ Leo H. Bartemeier (2011). Psychiatry and Public Affairs. Aldine Transaction. p. 246.

- ^ Clarke, Peter (2004). Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements. Routledge. p. 76.

- ^ Sherman, Fraser A. (2010). Screen Enemies of the American Way: Political paranoia about Nazis, Communists, Saboteurs, Terrorists and Body Snatching Aliens in Film and Television. McFarland.

- ^ Seed, David (2004). Brainwashing: A study in Cold War demonology. Kent State University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-87338-813-9.

- ^ Steven a.k.a. Superant. "Mind-control movies and TV". listal.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ Feeley, Malcolm M.; Rubin, Edward L. (2000). Judicial Policy Making and the Modern State: How the courts reformed America's prisons. Cambridge University Press. p. 268.

- ^ Ma, Sheng-mei (2012). Asian Diaspora and East-West Modernity. Purdue University Press. p. 129.

- ^ Wolfe, Gary K.; Williams, Carol T. (1983). "The Majesty of Kindness: The dialectic of Cordwainer Smith". In Clareson, Thomas D. (ed.). Voices for the Future: Essays on major science fiction writers. Vol. 3. Popular Press. pp. 53–72.

- ^ Schelde, Per (1994). Androids, Humanoids, and other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and soul in science fiction films. NYU Press. pp. 169–175. ISBN 978-0585321172.

- ^ O'Brien, Terry (2005). Westfahl, Gary (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. [ISBN missing]