Muhammad Ali vs. Sonny Liston

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (June 2023) |

The two fights between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston for boxing's World Heavyweight Championship were among the most controversial fights in the sport's history. Sports Illustrated magazine named their first meeting, the Liston–Clay fight (Ali had not yet changed his name from Cassius Clay), as the fourth greatest sports moment of the twentieth century.[1]

The first bout was held on February 25, 1964 in Miami Beach, Florida.[2] Clay, who was an 8:1 underdog, won in a major upset, when the champion gave up at the opening of the seventh round. Their second fight was on May 25, 1965 in Lewiston, Maine, which Ali won with a first-round knockout. The infamous "phantom punch", as well as a botched count by the referee, aroused suspicions of a fix and have been subject to debate ever since.

Liston vs. Clay I

[edit]Background

[edit]Liston was the World Heavyweight Champion at the time of the first Liston–Clay fight in Miami Beach on February 25, 1964, having demolished former champion Floyd Patterson by a first-round knockout in September 1962. Ten months later, Liston and Patterson met again with the same result – Patterson was knocked out in the first round.

At the time of the fight, Liston was generally considered the most intimidating fighter in the world, and among the best heavyweight boxers of all time. With the Patterson victory, Liston had defeated eight of the top 10 ranked contenders at heavyweight; seven of those victories were by knockout. Many were reluctant to meet him in the ring. Henry Cooper, the British champion, said he would be interested in a title fight if Clay won, but he was not going to get in the ring with Liston. Cooper's manager, Jim Wicks, said, "We don't even want to meet Liston walking down the same street."

Boxing promoter Harold Conrad said, "People talked about [Mike] Tyson before he got beat, but Liston was more ferocious, more indestructible. ... When Sonny gave you the evil eye—I don't care who you were—you shrunk [sic] to two feet tall."[3] Tex Maule wrote in Sports Illustrated: "Liston's arms are massively muscled, the left jab is more than a jab. It hits with true shock power. It never occurred to Liston that he might lose a fight."[3] Johnny Tocco, a trainer who worked with George Foreman and Mike Tyson as well as Liston, said Liston was the hardest hitter of the three.[4] Several boxing writers actually thought Liston could be damaging to the sport because he could not be beaten.[5] Liston's ominous, glowering demeanor was so central to his image that Esquire magazine caused a controversy by posing him in a Santa Claus hat for its December 1963 cover.

Liston learned to box in the Missouri State Penitentiary while serving time for armed robbery. Later, he was re-incarcerated for assaulting a police officer. For much of his career, his contract was majority owned by Frankie Carbo, a one-time mob hitman and senior member of the Lucchese crime family, who ran boxing interests for the Mafia. The mob was deeply entrenched in boxing at every level at the time, and Liston was never able to escape being labeled as the personification of everything that was unseemly and criminal in the sport, despite the fact that his criminality had been in the past. He distrusted boxing writers, and they paid him back, often depicting him as little more than an ignorant thug and a bully. He was typically described in thinly veiled racist terms—a "gorilla" and "hands like big bananas". Author James Baldwin understood Liston perhaps better than anyone in the press and sympathized with him and liked him, unlike boxing writers. He said "Liston was the big Negro in every white man's hallway." He was a man who, according to Ali biographer David Remnick, "had never gotten a break and was never going to give one".

On the other hand, Clay was a glib, fast-talking 22-year-old challenger who enjoyed the spotlight. Known as "The Louisville Lip", he had won the light heavyweight gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, Italy. He had great hand and foot speed and lightning fast reflexes, not to mention a limitless supply of braggadocio.[6] However, Clay had been knocked down by journeyman Sonny Banks early in his career, and, in his previous two fights, had eked out a controversial decision against Doug Jones and—more seriously—was knocked down by a left hook at the end of round four against the cut-prone converted southpaw Henry Cooper. Clay was clearly "out on his feet" in his corner between rounds, and his trainer, Angelo Dundee, stalled for time to allow Clay to recover. Although Clay rallied to win the fight in the next round, it seemed clear to many that he would be no match against the daunting Liston, who seemed a more complete boxer in every way than Cooper.

The brash Clay was equally disliked by reporters and his chances were widely dismissed. Lester Bromberg's forecast in the New York World-Telegram was typical, predicting, "It will last longer than the Patterson fight—almost the entire first round." The Los Angeles Times' Jim Murray observed, "The only thing at which Clay can beat Liston is reading the dictionary," adding that the face-off between the two unlikeable athletes would be "the most popular fight since Hitler and Stalin—180 million Americans rooting for a double knockout."[7] The New York Times' regular boxing writer Joe Nichols declined to cover the fight, assuming that it would be a mismatch. By fight time, Clay was an 8-to-1 betting underdog.[8] Of the 46 sportswriters at ringside, 43 had picked Liston to win by knockout.[9]

Liston, however, brought weaknesses into the Clay fight that were not fully apparent at the time. He claimed to be 32 years old at the time of the bout, but many believed that his true age was closer to 34, perhaps even older.[5] Liston had been suffering from bursitis in his shoulders for close to a year and had been receiving cortisone shots. In training for the Clay fight, he re-injured his left shoulder and was supposedly in pain striking the heavy bag. He secretly resorted to heavy icing and ultrasound therapy after each training session. And, ironically, because of his dominance, Liston had actually logged little ring time in the past three years. Between March 1961 and the Clay fight, Liston had fought three times and won each bout with first-round knockouts—meaning that he had fought a total of just over six minutes during a 35-month stretch.[5]

One of the reasons that Clay's chances were dismissed is that his boxing style seemed ill-suited to the heavyweight division. He was widely viewed as a fast but light puncher lacking the ability to take a punch or to fight inside. The signatures of Clay's style and later greatness—the tendency to keep his hands low and lean away from punches (often leaving his opponent hitting air, off balance, and exposed to counter punches), his constant movement and reluctance to set (making him extremely difficult to hit)—were viewed as fundamental technical flaws that would be quickly exploited by an experienced, hard-hitting heavyweight like Liston. New York Journal-American columnist Jimmy Cannon summarized this view when he wrote: "Clay doesn't fight like the valid heavyweight he is. He seldom sets and misses a lot. In a way, Clay is a freak. He is a bantamweight who weighs more than 200 pounds [91kg]."

Liston trained minimally for the bout, convinced that he would dispose of Clay within the first two rounds. He typically ran just one mile a day instead of his usual five, reportedly ate hot dogs and drank beer, and was rumored to have been furnished with prostitutes in training camp.[10]

Pre-fight publicity

[edit]The television series I've Got a Secret did multiple segments about the title fight. Panelists Bill Cullen, Henry Morgan and Betsy Palmer predicted that Liston would win in the third, second, and first rounds, respectively. Host Garry Moore was even more pessimistic about Clay's chances, estimating a Liston knockout "in the very early moments of round one", adding, "if I were Cassius, I would catch a cab and leave town." Actor Hal March went a step further, albeit humorously: "I think the fight will end in the dressing room. I think [Clay] is going to faint before he comes out."

The night before the first fight, on February 24, 1964, the show featured Clay and Liston's sparring partners as guests.[11] Harvey Jones brought with him a lengthy rhyming boast from Cassius Clay:

Clay comes out to meet Liston and Liston starts to retreat,

If Liston goes back an inch farther he'll end up in a ringside seat.

Clay swings with a left,

Clay swings with a right,

Just look at young Cassius carry the fight.

Liston keeps backing but there's not enough room,

It's a matter of time until Clay lowers the boom.

Then Clay lands with a right, what a beautiful swing,

And the punch raised the bear clear out of the ring.

Liston still rising and the ref wears a frown,

But he can't start counting until Sonny comes down.

Now Liston disappears from view, the crowd is getting frantic

But our radar stations have picked him up somewhere over the Atlantic.

Who on Earth thought, when they came to the fight,

That they would witness the launching of a human satellite.

Hence the crowd did not dream, when they laid down their money,

That they would see a total eclipse of Sonny.— Cassius Clay, as read on CBS' I've Got a Secret[11]

Clay also presented that poem on The Jack Paar Show with Liberace giving improvised piano harmony.

Jesse Bowdry brought a much terser written message from Sonny Liston:

Cassius, you're my million dollar baby, so please don't let anything happen to you before tomorrow night.

— Sonny Liston, as read on CBS' I've Got a Secret[11]

The following week, I've Got a Secret brought on two sportswriters whose secret was that they had been the only writers to correctly predict Clay's victory.

Baiting the bear

[edit]Clay began taunting and provoking Liston almost immediately after the two agreed to fight. He purchased a bus and had it emblazoned with the words "Liston Must Go In Eight". On the day of the contract signing, he drove it to Liston's home in Denver, waking the champion (with the press in tow) at 3:00 a.m. shouting, "Come on out of there. I'm gonna whip you now." Liston had just moved into a white neighborhood and was furious at the attention this caused. Clay took to driving his entourage in the bus to the site in Surfside, Florida where Liston (nicknamed the "Big Bear") was training, and repeatedly called Liston the "big, ugly bear".[7] Liston grew increasingly irritated as the motor-mouthed Clay continued hurling insults: "After the fight, I'm gonna build myself a pretty home and use him as a bearskin rug. Liston even smells like a bear. I'm gonna give him to the local zoo after I whup him ... if Sonny Liston whups me, I'll kiss his feet in the ring, crawl out of the ring on my knees, tell him he's the greatest, and catch the next jet out of the country." Clay insisted to a skeptical press that he would knock out Liston in eight rounds (former light heavyweight champion José Torres, in his 1971 biography of Ali, Sting Like a Bee, said that as of 1963, Ali's prophetic poems had correctly predicted the exact round he would stop an opponent 12 times).

Clay's brashness did not endear him to white Americans, and, in fact, even made Liston a more sympathetic character. In The New Republic, the editor Murray Kempton wrote, "Liston used to be a hoodlum; now he is our cop; he was the big Negro we pay to keep sassy Negroes in line."[12]

It has been widely stated that Clay's antics were a deliberate form of psychological warfare designed to unsettle Liston by stoking his anger, encouraging his overconfidence and even fueling uncertainty about Clay's sanity. As Clay himself said, "If Liston wasn't thinking nothing but killing me, he wasn't thinking fighting. You got to think to fight." Former World Heavyweight Champion Joe Louis said, "Liston is an angry man, and he can't afford to be angry fighting Clay." Clay's outbursts also fed Liston's belief that Clay was terrified (something Clay's camp did little to disavow). Clay said later, "I knew that Liston, overconfident that he was, was never going to train to fight more than two rounds. He couldn't see nothing to me at all but mouth."[10] In contrast, Clay prepared hard for the fight, studying films of Liston's prior bouts and even detecting that Liston telegraphed his punches with eye movement.[13]

The Nation of Islam

[edit]Several weeks before the fight, the Miami Herald published an article quoting Cassius Clay Sr. as saying that his son had joined the Black Muslims when he was 18. "They have been hammering at him ever since," Clay Sr. said. "He's so confused now that he doesn't even know where he's at." He said his youngest son, Rudy Clay, had also joined. "They ruined my two boys," Clay Sr. said. "Muslims tell my boys to hate white people; to hate women; to hate their mother." Clay Jr. responded by saying, "I don't care what my father said. ... I'm here training for a fight, and that's all I'm going to say."[14]

As the story began to spread, promoters became increasingly uneasy. Bill MacDonald, the main promoter, threatened to cancel the fight unless Clay publicly disavowed the Nation of Islam (NOI). Clay refused. A compromise was reached when Malcolm X, at the time a companion of Clay's as well as a feared and incendiary spokesperson for the Nation of Islam (though Malcolm X had, by that time, been censured by the NOI—banned from speaking to the press and suspended from all official NOI roles and duties—and would soon officially break with the Nation), agreed to keep a low profile, save for the night of the fight when he would rejoin Clay's entourage as spiritual advisor and view the fight from a ringside seat. While Clay would not definitively link himself with the Nation of Islam and its leader, Elijah Muhammad, until the day after the fight—at the annual NOI Savior's Day celebration—his association with the Nation, seen by many as a hate group due in part to its strict anti-integrationist stance, further complicated his relations with the press and the white public, further deprived the fight of the "good guy/bad guy" narrative, and negatively affected the gate. MacDonald would ultimately lose $300,000 on the bout.[15]

According to Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali had converted to Islam and joined the Nation of Islam several years prior to the fight, but had kept his religion and affiliation a secret up until the fight.[16]

The weigh-in

[edit]Ali's outbursts reached their peak at the pre-fight weigh-in/physical the morning of the event. Championship bout weigh-ins, before this, had been predictable and boring. Ali entered the room where the weigh-in would be held wearing a denim jacket with the words "Bear Huntin'" on the back and carrying an African walking stick. He began waving the stick, screaming, "I'm the champ! Tell Sonny I'm here. Bring that big ugly bear on." When Liston appeared, Ali went wild. "Someone is going to die at ringside tonight!" he shouted. "You're scared, chump!" He was restrained by members of his entourage. Writer Mort Sharnik thought Ali was having a seizure. Robert Lipsyte, the New York Times writer, likened the scene to a "police action, with an enormous amount of movement and noise exploding in a densely packed room." Amidst the pandemonium, he was fined $2,500 by the commission for his behavior.[17] Ali worked himself into such a frenzy that his heart rate registered 120 beats per minute, more than twice its normal rate, and his blood pressure was 200/100. Dr. Alexander Robbins, the chief physician of the Miami Boxing Commission, determined that he was "emotionally unbalanced, scared to death, and liable to crack up before he enters the ring." He said if Ali's blood pressure didn't return to normal, the fight would be canceled.[18] Many others also took Clay's antics to mean that he was terrified. In fact, a local radio station later reported a rumor that he had been spotted at the airport buying a ticket to leave the country.[19] A second examination conducted an hour later revealed Ali's blood pressure and pulse had returned to normal. It had all been an act. Ali later said, "Liston's not afraid of me, but he's afraid of a nut."[20]

The fight

[edit]| Date | February 25, 1964 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venue | Convention Hall Miami Beach, Florida[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Title(s) on the line | WBA, WBC, NYSAC, and The Ring heavyweight titles | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tale of the tape | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Result | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ali wins via 6th-round RTD | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Clay weighed in at 210+1⁄2 lb (95 kg) while Liston was several pounds over his prime fighting weight at 218 lb (99 kg).[17] Many of those watching were surprised during the referee's instructions to see that Clay was considerably taller than Liston. While receiving instructions, Liston glowered at Clay, while Clay stared back and stood on his toes to appear even taller. Clay later said of the moment: "I won't lie, I was scared ... It frightened me, just knowing how hard he hit. But I didn't have no choice but to go out and fight."[3]

At the opening bell, an angry Liston charged Clay, looking to end the fight quickly and decisively. However, Clay's superior speed and movement were immediately evident, as he slipped most of Liston's lunging punches, making the champion look awkward. Clay clearly gained confidence as the round progressed. He hit Liston with a combination that electrified the crowd with about 30 seconds left in the round and began scoring repeatedly with his left jab (the round lasted an extra 8.5 seconds because referee Barney Felix didn't hear the bell). Clay had been hit hard by a right to the stomach, but he said later, "I felt good because I knew I could survive." Milt Bailey, one of Liston's cornermen, recalled, "In the first round Sonny couldn't catch up with Clay, and I thought we might have some trouble."[22] Indeed, it was perhaps the worst round of Liston's career.[10] Between rounds, sitting on his stool, Clay turned to the press contingent at ringside and opened his mouth as if yawning or making a mute roar.

Liston settled down somewhat in round two. At one point, he cornered Clay against the ropes and hit him with a hard left hook. Clay later confessed that he was hurt by the punch, but Liston failed to press his advantage. Two of the official scorers awarded the round to Liston and the other had it even.

In the third round, Clay began to take control of the fight. At about 30 seconds into the round, he hit Liston with several combinations, causing a bruise under Liston's right eye and a cut under his left, which eventually required eight stitches to close. It was the first time in his career that Liston had been cut. At one point in this attack, Liston was rocked as he was driven to the ropes.[23] Les Keiter, broadcasting at ringside, shouted, "This could be the upset of the century!" Mort Sharnik described the moment: "Cassius hit Liston with a one-two combination; a jab followed by a straight right. Cassius pulled the jab back and there was a mouse underneath Sonny's right eye. Then he pulled the right back and there was a gash underneath the other eye. ... It was like the armor plate of a battleship being pierced. I said to myself, 'My God, Cassius Clay is winning this fight!'"[24] A clearly angered Liston rallied at the end of the round, as Clay seemed tired, and delivered punishing shots to Clay's body. It was probably Liston's best moment in the entire fight. But as the round ended, Clay shouted to him, "you big sucka, I got you now".[25] Sitting on his stool between rounds, Liston was breathing heavily as his cornermen worked on his cut.

During the fourth round, Clay coasted, keeping his distance and Liston appeared dominant. Joe Louis commenting on TV at ringside said "It's looking good for Sonny Liston". However, when Clay returned to his corner, he started complaining that there was something burning in his eyes and he could not see. "I didn't know what the heck was going on," Angelo Dundee, Clay's trainer, recalled on an NBC special 25 years later. "He said, 'cut the gloves off. I want to prove to the world there's dirty work afoot.' And I said, 'whoa, whoa, back up baby. C'mon now, this is for the title, this is the big apple. What are you doing? Sit down!' So I get him down, I get the sponge and I pour the water into his eyes trying to cleanse whatever's there, but before I did that I put my pinkie in his eye and I put it into my eye. It burned like hell. There was something caustic in both eyes."

The commotion wasn't lost on referee Barney Felix, who was walking toward Clay's corner. Felix said Clay was seconds from being disqualified.[10] The challenger, his arms held high in surrender, was demanding that the fight be stopped and Dundee, fearing the fight might indeed be halted, gave his charge a one-word order: "Run!"

Clay later said he could only see a faint shadow of Liston during most of the round, but by circling and moving he managed to avoid Liston and somehow survive. By the sixth round, Clay's sight had cleared, and he began landing combinations almost at will. "I got back to my stool at the end of the sixth round, and under me I could hear the press like they had gone wild," Clay later said. "I twisted round and hollered down at the reporters, 'I'm gonna upset the world.'" [26]

There are two basic narratives about what occurred next in Liston's corner. According to Ali biographer David Remnick, Liston told his cornermen, "That's it." This supposedly rallied Liston's handlers, who thought he meant he was finally angry enough to win, but Liston really meant that he was through fighting, which he indicated by spitting out his mouth guard.

However, Liston biographer Paul Gallender's take is that Liston's shoulder was essentially paralyzed by the end of round six, and his corner made the decision to end the fight, despite Liston's protests. Liston spit out his mouth guard in disgust, still not believing that Clay was the superior fighter.

As the bell sounded for the seventh round, Clay was the first to notice that Liston had spat out his mouth guard. Clay moved to the middle of the ring with his arms raised, dancing the jig that would become known as the "Ali Shuffle" while Howard Cosell, broadcasting at ringside, shouted "wait a minute! Wait a minute! Sonny Liston is not coming out!" Liston failed to answer the bell for the seventh round, and Clay was declared the winner by technical knockout. Liston became the first World Champion since Jess Willard in 1919 to retire on his stool during a Heavyweight title fight. At that point the bout was level on the official scorecards of the referee and two judges.[27][28]

Sensing that he had made history, Clay quickly ran to the ropes amidst the commotion in the ring and shouted at sportswriters, "Eat your words!" In a scene that has been rebroadcast countless times over the ensuing decades, Clay repeatedly yelled "I'm the greatest!" and "I shook up the world."

Clay had to be persuaded to hold the traditional post-fight press conference. He called the writers "hypocrites" and said, "Look at me. Not a mark on me. I could never be an underdog. I am too great. Hail the champion!"[29]

On February 27, 1964, Clay announced that he was a member of the Nation of Islam. His membership in the group was first disclosed the previous night at the group's annual national convention in Chicago by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad.

"I began worshiping this way five years ago when I heard a fellow named Elijah Muhammad on the radio talking about the virtues of the Islam religion," Clay said. "I also listened to his ministers. No one could prove him or them wrong, so I decided to join."

Clay started going by the name Cassius X, as members of the organization adopt the last name X because they no longer want to bear names handed down by former slave-owning families.[30]

On March 1, 1964, Ed Sullivan said on his show: "I saw the Liston-Clay fight. This was a stinker of all-time. I swear The Beatles could beat the two of 'em! No kidding!" The Beatles had been on The Ed Sullivan Show twice in February. During their second appearance, which aired February 16 from Miami, Sullivan actually had Liston and Joe Louis—who were in the audience—stand up for applause; the group also visited Clay's training center later in the week.[31]

On March 6, 1964, Elijah Muhammad announced in a recorded statement played over the radio that Clay would be renamed Muhammad Ali. Muhammad means "worthy of all praises", and Ali means "most high".[32]

Did Liston's corner deliberately blind Clay?

[edit]Many theorized that a substance used on Liston's cuts by Joe Pollino, his cutman, may have inadvertently caused the irritation that blinded Clay in round four. "Joe Pollino had used Monsel's Solution on that cut," Angelo Dundee said. "Now what had happened was that probably the kid put his forehead leaning in on the guy—because Liston was starting to wear in with those body shots—and my kid, sweating profusely, it went into both eyes."

Two days after the fight, heavyweight contender Eddie Machen said he believed that Liston's handlers made deliberate use of illegal medication to temporarily blind Clay. "The same thing happened to me when I fought Liston in 1960," Machen said. "I thought my eyes would burn out of my head, and Liston seemed to know it would happen." He theorized that Liston's handlers would rub medication on his shoulders, which would then be transferred to his opponent's forehead during clinches and drip into the eyes. "Clay did the worst thing when he started screaming and let Liston know it had worked," Machen said. "Clay panicked. I didn't do that. I'm more of a seasoned pro, and I hid it from Liston." [33] It is noteworthy that Machen did not mention the eye burning problem immediately after his fight with Liston, citing an injury to his arm as contributing to his defeat.[34]

Shoulder injury

[edit]Liston said he quit the fight because of a shoulder injury, and there has been speculation since about whether the injury was severe enough to actually prevent him from continuing. Immediately after the fight, Liston told broadcasters that he hurt the shoulder in the first round. Dr. Alexander Robbins, chief physician for the Miami Beach Boxing Commission, diagnosed Liston with a torn tendon in his left shoulder.

For his book, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero, David Remnick spoke with one of Liston's cornermen, who told him that Liston could have continued: "[The shoulder] was all BS. We had no return bout clause with Clay, and if you say your guy just quit, who is gonna get a return bout. We cooked up that shoulder thing on the spot."[35]

Sports Illustrated writer Tex Maule wrote that Liston's shoulder injury was legitimate. He cited Liston's inability to lift his arm: "There is no doubt that Liston's arm was damaged. In the sixth round, he carried it at belt level so that it was of no help in warding off the right crosses with which Clay probed at the cut under his left eye." He also cited medical evidence: "A team of eight doctors inspected Liston's arm at St. Francis Hospital in Miami Beach and agreed that it was too badly damaged for Liston to continue fighting. The torn tendon had bled down into the mass of the biceps, swelling and numbing the arm."[36]

Those findings were confirmed in a formal investigation immediately after the fight by Florida State Attorney Richard Gerstein, who also noted that there was little doubt that Liston went into the fight with a sore or lame shoulder.[37] Despite Liston carrying an injury and being undertrained, Ali stated in 1975 that this fight was his toughest ever.[38]

Allegations of a fix

[edit]There were allegations of a fix as soon as the fight ended. Arthur Daley of the New York Times did not believe the claim. He wrote:

- When a fight ends in the fashion this one did, with the unbeatable monster remaining in his corner, suspicions of larceny are immediately aroused. They are not helped by the fact that Liston, an ex-convict, was sponsored by mobsters at the start of his career. For the larceny theory to be valid, however, there would have to be an overwhelming reason for it. The prospects of a betting coup can be dismissed because the 8-to-1 odds in Liston's favor never varied more than a point. If there had been a rush of smart money on the underdog, the odds would have plummeted. This is an unfailing barometer of hanky-panky. What would Liston have gained by throwing the fight? The heavyweight championship is the most valuable commodity in the world of sports and not even a man of Liston's criminal background would willingly toss it away. It also brought him an aura of respectability such as he never had known before.[39]

After a month-long investigation, Florida State Attorney Richard E. Gerstein said there was no evidence to support the claim of a fix, and a United States Senate subcommittee conducted hearings three months later and also found no evidence of a fix.

Documents were released to the Washington Times in 2014 under the Freedom of Information Act which show the FBI suspected the fight may have been fixed by Ash Resnick, a Las Vegas figure tied to organized crime and to Liston. The documents show no evidence that Ali was in on the scheme or even knew about it, and nothing suggests the bureau ever corroborated the suspicions it investigated.[40] The memos were addressed directly to Director J. Edgar Hoover.

A memo dated May 24, 1966, which the Washington Times called "the most tantalizing evidence," details an interview with a Houston gambler named Barnett Magids, who described to agents his discussions with Resnick before the first Clay-Liston fight. The Washington Times reported:

- "On one occasion, Resnick introduced Magids to Sonny Liston at the Thunderbird, [one of the Las Vegas hotels organized crime controlled]," the memo states. "About a week before the Liston and Clay fight in Miami, Resnick called and invited Magids and his wife for two weeks in Florida on Resnick. Magids' wife was not interested in going, but Magids decided to go along, and Resnick was going to send him a ticket.

- "Two or three days before the fight, Magids called Resnick at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami to say he could not come," the memo states. "On this call, he asked Resnick who he liked in the fight, and Resnick said that Liston would knock Clay out in the second round. Resnick suggested he wait until just before the fight to place any bets because the odds may come down.

- "At about noon on the day of the fight, [Magids] reached Resnick again by phone, and at this time, Resnick said for him to not make any bets, but just go watch the fight on pay TV and he would know why and that he could not talk further at that time.

- "Magids did go see the fight on TV and immediately realized that Resnick knew that Liston was going to lose," the document states. "A week later, there was an article in Sports Illustrated writing up Resnick as a big loser because of his backing of Liston. Later people 'in the know' in Las Vegas told Magids that Resnick and Liston both reportedly made over $1 million betting against Liston on the fight and that the magazine article was a cover for this."[41]

The article was controversial, with Ron Kantowski of the Las Vegas Review-Journal writing that the Washington Times article "had more holes than the left side of the Cubs' infield." He continued:

- Here, then, is the most titillating part of the Washington Times story: "At about noon on the day of the fight, (Barnett Magids) reached Resnick again by phone, and at this time, Resnick said for him to not make any bets, but just go watch the fight on pay TV, and he would know why ..."

- This was after the weigh-in, when Ali went berserk and Sonny just burped up a couple of ... hot dogs.

- Is it possible this is why Ash Resnick might have told Barnett Magids—according to Magids—not to make any bets on Liston?

- According to a Sports Illustrated story, Resnick lost a lot of money betting on Liston. ... The Washington Times' story suggested ... the magazine story may have been a cover-up, quoting "people in the know."

- Sometimes in boxing, a guy trains on hot dogs and beer, and then maybe he injures his shoulder. A guy everybody expects to win, doesn't win. And then there are FBI files and conspiracy theories, and then "people in the know" want to put a guy like Sonny Liston on the grassy knoll with a smoking gun in his hand.[42]

Ali vs. Liston II

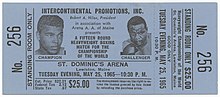

[edit] Original ticket for Ali-Liston II | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | May 25, 1965 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venue | Central Maine Youth Center Lewiston, Maine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Title(s) on the line | WBC, NYSAC, and The Ring heavyweight titles | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Tale of the tape | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Result | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ali wins via 1st-round KO | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Background

[edit]Following Clay's upset victory over Liston, both fighters were almost immediately embroiled in controversy that was considered detrimental to the sport of boxing. A couple of days after the fight, Clay publicly announced that he had joined the "Black Muslims"—which at the time was widely viewed as a hate group against white people—and started going by the name Cassius X. The following month, he was renamed Muhammad Ali by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. This evoked widespread public condemnation. Martin Luther King Jr. said, "When Cassius Clay joined the Black Muslims and started calling himself Cassius X, he became a champion of racial segregation."[44] As for Liston, he was arrested on March 12 and charged with speeding, careless and reckless driving, driving without an operator's license and carrying a concealed weapon. The arresting officer said the former champion was driving between 76 and 80 mph (122–129 km/h) in a residential zone. Liston had a loaded .22 caliber revolver in his coat pocket and there were empty bottles of vodka in the car. A young woman was in the car with Liston, but she was not arrested.[45] In short, at a time when Congress was investigating corruption and organized crime influence in boxing, neither fighter was seen as a poster child for the sport.

In the view of some, the unexpected ending of the bout took on suspicious overtones when it was discovered that the two fighters had a contract which contained a rematch clause. Many argued that Liston had more to gain financially from losing the bout and fighting a rematch than he did from winning. The contract gave Inter-Continental Promotions, Inc., a firm organized to promote Liston's fights, the right to promote Ali's first fight as champion—if he should beat Liston—and pick his opponent (Liston, of course). This was in a second contract, kept secret and not part of the main fight contract. It was phrased as it was because the World Boxing Association did not allow fight contracts with rematch clauses. Gordon B. Davidson, an attorney for the group sponsoring Ali, said, "We felt we would be better advised not to have a guaranteed rematch clause. We felt this was more in the spirit of the WBA rules than a direct rematch which was clearly outlawed." He agreed that it was "subterfuge".[46] When Ali and Liston signed to fight a rematch, the WBA voted unanimously to strip Ali of the title and drop Liston from its rankings. However, the World Boxing Council, the New York State Athletic Commission and The Ring magazine continued to recognize Ali as champion.

Pressed by the WBA—which included every U.S. state except California, Nevada and New York—state boxing commissions throughout the nation were reluctant to license a rematch between the two controversial fighters, and it was difficult to find a venue. Ultimately, Massachusetts agreed to host the bout, which resulted in the suspension of the Massachusetts Boxing Commission by the WBA. The fight was set for November 16, 1964, at the Boston Garden. Liston was immediately established as a 13:5 favorite, making Ali a greater betting underdog than Floyd Patterson in his two fights against Liston. This time, Liston trained hard, preparing himself for a 15-round bout. In fact, Time magazine said that Liston had worked himself into the best shape of his career.[47] Ali, for his part, continued to taunt Liston, dragging a bear trap to the pre-fight physical and announcing that he might begin manufacturing the "Sonny Liston Sit-Down Stool". However, the Boston fight would never occur. Three days before the scheduled bout (on a Friday the 13th, as it happened), Ali needed emergency surgery for a strangulated hernia. The bout would need to be delayed by six months.

The new date was set for May 25, 1965. But as it approached, Liston was involved in yet another arrest and there were fears that the promoters were tied to organized crime. Massachusetts officials, most notably Suffolk County District Attorney Garrett H. Byrne, began to have second thoughts. Byrne sought an injunction blocking the fight in Boston because Inter-Continental Promotions was promoting the fight without a Massachusetts license. Inter-Continental said local veteran Sam Silverman was the promoter. On May 7, backers of the rematch ended the court battle by pulling the fight out of Boston.[48]

Lewiston, Maine

[edit]

The promoters needed a new location quickly, whatever the size, to rescue their closed circuit television commitment around the country. Governor John H. Reed of Maine stepped forward, and within a few hours, the promoters had a new site: Lewiston, Maine, a mill town with a population of about 41,000 located 140 miles (230 km) north of Boston. Inter-Continental obtained a permit and made an arrangement to work with local promoter Sam Michael. The venue selected was the Central Maine Youth Center (now called The Colisée), a junior hockey rink. Lewiston was the smallest city to host a heavyweight title bout since Jack Dempsey fought Tom Gibbons in Shelby, Montana (population 3,000) in 1923. It remains the only heavyweight title fight held in the state of Maine.

The fight was embraced by the Pine Tree State. Governor Reed announced to the press, "This is one of the greatest things to happen in Maine."[49] Nevertheless, it would go down in history as a debacle.

The atmosphere surrounding the fight was tense and sometimes ugly, largely due to the repercussions of Ali's public embrace of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam.[15] Malcolm X, who had a public and bitter falling out with Elijah Muhammad, had been assassinated several months before the fight, and the men arrested for the slaying were members of the Nation of Islam. Rumors circulated that Ali, who had publicly snubbed Malcolm after his break with Elijah Muhammad, might be killed by Malcolm's supporters in retaliation. The FBI took the threats seriously enough to post a 12-man, 24-hour guard around Ali. Liston's camp, in turn, claimed he had received a death threat from the Nation of Islam. The Fruit of Islam—the omnipresent, bow-tied paramilitary wing of the Nation of Islam—surrounding Ali only added to the sense of foreboding and hostility. Security for the fight was unprecedented.

The phantom/anchor punch

[edit]The ending of the second Ali-Liston fight remains one of the most controversial in boxing history. Midway through the first round, Liston threw a left jab and Ali supposedly went over it with a fast right, knocking the former champion down. Liston went down on his back. He rolled over, got to his right knee and then fell on his back again. Many in attendance did not see Ali deliver the punch. The fight quickly descended into disarray. Referee Jersey Joe Walcott, a former World Heavyweight Champion himself, had a hard time getting Ali to go to a neutral corner. Ali initially stood over his fallen opponent, gesturing and yelling at him, "Get up and fight, sucker!" and "Nobody will believe this!"[23] The moment was captured by ringside photographer Neil Leifer in what became one of the most iconic images in sport,[50] chosen as the cover of the Sports Illustrated special issue, "The Century's Greatest Sports Photos". Ali then began prancing around the ring with his arms raised in victory.

When Walcott got back to Liston and looked at the knockdown timekeeper, Francis McDonough, to pick up the count, Liston had fallen back on the canvas. Walcott never did pick up the count. He said he could not hear McDonough, who did not have a microphone. Also, McDonough did not bang on the canvas or motion a number count with his fingers. McDonough, however, claimed Walcott was looking at the crowd and never at him. After Liston arose, Walcott wiped off his gloves. He then left the fighters to go over to McDonough. "The timekeeper was waving both hands and saying, 'I counted him out—the fight is over'", Walcott said after the fight. "Nat Fleischer [editor of The Ring] was seated beside McDonough and he was waving his hands, too, saying it was over." Walcott then rushed back to the fighters, who had resumed boxing, and stopped the fight—awarding Ali a first-round knockout victory.[51]

It is one of the quickest heavyweight title knockouts in history. Many in the small crowd had not even settled in their seats when the fight was stopped. The official time of the stoppage was announced as 1:00 into the first round, which was wrong. Liston went down at 1:44, got up at 1:56, and Walcott stopped the fight at 2:12.

McDonough and Fleischer were also wrong in their interpretation of how the rules applied. Under the rules, the timekeeper is supposed to start the count at the time of a knockdown. The referee's duty is to get the boxer scoring the knockdown to a neutral corner, pick up the count from the timekeeper and continue it aloud for the knocked down boxer. Under the rules of the Maine Commission, the referee was authorized to stop his count if a boxer refused to go to the proper corner. "It might have been better if Walcott had stopped the count (by the knockdown timekeeper) until Clay went to the neutral corner and then started again," said Duncan MacDonald, a commission member.[52]

"I did my job," Walcott said. "He [Ali] looked like a man in a different world. I didn't know what he might do. I thought he might stomp him or pick him up and belt him again."

"If that bum Clay had gone to a neutral corner instead of running around like a maniac, all the trouble would have been avoided," McDonough said. He acknowledged that Walcott could have asked him to start the count again "after he got that wild man—Clay—back to a neutral corner, but he didn't, so that was that."[53]

Alleged match fixing

[edit]When the fight ended, numerous fans booed and started yelling, "Fix!" Skeptics called the knockout blow "the phantom punch". Ali called it "the anchor punch". He said it was taught to him by comedian and film actor Stepin Fetchit, who learned it from Jack Johnson. However, Ali was unsure immediately after the fight as to whether or not the punch connected, as footage from the event shows Ali in the ring asking his entourage, "Did I hit him?" Ali told Nation of Islam minister Abdul Rahman that Liston "laid [sic] down" and Rahman replied, "No, you hit him." Rahman later said, "Ali hit him so fast, Ali didn't really know he hit him. ... and it took a long time before even he saw the punch he hit Sonny with."[54] Ali never used the "anchor punch" in subsequent fights, nor did he mention it in later discussions about his career.[27] This has led to ongoing debates about the nature and impact of the punch, as well as the legitimacy of Liston's fall.

After the fight, George Chuvalo climbed through the ropes and shoved Ali, yelling, "Fix!" He was restrained, but later he said that he had seen Liston's eyes while the challenger was on the floor, and he knew that he was not in bad shape. "His eyes were darting from side to side like this," he said, darting his eyes from side to side. "When a fighter is hurt his eyes roll up."

There were some at ringside who believed the fight was legitimate. Larry Merchant, who was a critic of Liston as a person throughout his career,[55][56] wrote 50 years later, "I saw the actual punch land on the actual chin, as did others in my area of the press section. It was a quick right hand that caught Liston as he was coming forward ... According to ringside doctors I've spoken to, that is a classic example of a medulla oblongata K.O."[57] World Light Heavyweight Champion José Torres said, "It was a perfect punch."[citation needed] Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote[when?] that it was "no phantom punch". Tex Maule of Sports Illustrated wrote, "The blow had so much force it lifted Liston's left foot, upon which most of his weight was resting, well off the canvas."

"Many people in the arena did not see [the punch], understandably", Merchant wrote: "Or they couldn't believe that it had the force to knock out the seemingly indestructible former champion". He described the belief that the fight was rigged as "the apparently unkillable myth ... many people believe that the moon landings were staged, probably right there in Lewiston".[57] Slow motion examination of the fight recording shows that the 'punch' that landed was a short grazing right to Liston's cheek and of apparently limited power.[23] Hall of Fame announcer Don Dunphy was one of many who didn't believe the fight was on the level. "If that was a punch, I'll eat it," he said. "Here was a guy who was in prison and the guards [used] to beat him over the head with clubs and couldn't knock him down." But others contend that he wasn't the same Liston. Dave Anderson of the New York Times said Liston "looked awful" in his last workout before the fight. Liston's handlers secretly paid sparring partner Amos Lincoln an extra $100 to take it easy on him. Arthur Daley of the New York Times wrote that Liston's handlers knew he "didn't have it anymore". These statements do not accord with the fact that three years later Liston easily knocked out Lincoln within two rounds.[58]

One ringside observer, former World Heavyweight Champion James J. Braddock, said the suspect Ali right hand merely finished up what an earlier punch had begun. "I have a feeling that this guy (Ali) is a lot better than any of us gave him credit for," Braddock said. "It isn't the knockout punch that sticks in my mind as much as a punch he let go (earlier). ... It was a right to Liston's jaw and it shook him to his shoetops. For all we know, it could have been the one that set up the knockout."

Another former champion, Rocky Marciano, changed his view about the knockout punch after seeing videotape the next day. "I didn't think it was a powerful punch when I saw the fight from ringside," Marciano said. "Now (after seeing video) I think Clay, seeing the opening, snapped the punch the last six inches."[59] He added that he still didn't think it was a knockout punch.

Ali did not think he knocked Liston out. In his own words in Thomas Hauser's 1991 biography: "The punch jarred him. It was a good punch, but I didn't think I hit him so hard that he couldn't have gotten up. Once he went down, I got excited. I forgot about the rules". In that same book, Liston, quoted two years after the fight: "Ali knocked me down with a sharp punch. I was down but not hurt, but I looked up and saw Ali standing over me. ... Ali is waiting to hit me, the ref can't control him".[60]

Dave Anderson said he saw Liston in Las Vegas in 1967 and asked him what happened. "It wasn't that hard a punch, but it partially caught me off balance and when I got knocked down, I got mixed up because the referee never gave me a count," Liston said. "I was listening for a count. That's the first thing you do, but I never heard a count because Clay never went to a neutral corner."

Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger said Liston told him that he lost simply because "the timekeeper couldn't count".

Mark Kram of Sports Illustrated said Liston told him: "That guy [Ali] was crazy. I didn't want anything to do with him. And the Muslims were coming up. Who needed that? So I went down. I wasn't hit."

Wilfred Sheed offered his opinion in his 1975 book, Muhammad Ali: A Portrait in Words and Photographs, writing that Liston was going to throw the fight going in and, when he suffered a legitimate flash knockdown in round one, decided on the spot to seize the opportunity and end the fight. It was Walcott's confusion and Ali's behavior that forced Liston to feign disorientation for far longer than a knockdown of that type would have caused.

During a 1995 HBO documentary about Liston, Johnny Tocco, who owned a boxing gym in Las Vegas, said he spoke with mobster John Vitale before the rematch and was told not to pay any attention to what he heard about the fight. He also told Tocco that he should be glad that he was not going to Lewiston. When Tocco asked why, Vitale told him that the fight was going to end in the first round.

During the same documentary, former FBI agent William F. Roemer Jr. said, "We learned that there very definitely had been a fix in that fight." He said Bernie Glickman, a boxing manager from Chicago with mob ties, claimed that while he was conversing with Liston and his wife before the fight, Liston's wife told the ex-champion that as long as he had to lose the fight, he should go down early to avoid any chance of getting hurt.

In the wake of the controversial fight, there was an outcry by press and politicians for the abolition of boxing. Bills to ban the sport were planned in several state legislatures.

A promoter in San Antonio apologized to his theater TV customers and, on the basis that they had been defrauded by a "shameful spectacle", donated his take to boys' clubs. The California legislature, in session, received a resolution calling for an investigation by the state attorney general to determine if its closed-circuit viewers had been fraudulently duped out of their money.[61]

For those who believe that Liston took a dive, there are a number of theories as to why, including:

- The Mafia forced Liston to throw the fight as part of a betting coup.

- Liston bet against himself and took a dive because he owed money to the Mafia.

- A couple of members of the Nation of Islam visited Liston's training camp and told Liston they would kill him if he won the rematch.

- Author Paul Gallender claims that members of the Nation of Islam kidnapped Liston's wife, Geraldine, and Liston's son, Bobby. Liston was told to lose the fight to Ali or he would never see his family again.[62]

- Liston was afraid that he would be accidentally shot by followers of Malcolm X as they tried to kill Ali in the ring. There were also claims attributed to Liston and others that he threw the fight in return for a share of the more marketable Ali's future purses.[63] Credence to these claims is provided by the fact that after his last fight, with Chuck Wepner, Liston seemed more preoccupied in supporting the proposed Ali-Frazier bout and Ali's claims to the title than about his own career.[64]

In the final analysis, it remains inconclusive whether the blow in Lewiston was a genuine knockout punch.[65] The fact that Liston did not complain about the clear breach of boxing rules (being declared knocked out without a count) and Ali's obvious state of bewilderment, shouting at Liston "Nobody will believe this" and asking his handlers "Did I hit him?" is viewed as confirmation for most people's belief that Liston took a dive.[66]

Legacy

[edit]The two bouts launched one man and ruined the other.

The fight contributed to the Ali mystique of beating seemingly insurmountable foes. For Liston, the fights left his reputation in tatters. In just a little over one year, he went from being considered one of the most fearsome heavyweights of all-time to an overrated champion. "[After the two Ali fights] Liston would never again intimidate a world-class fighter," wrote Bob Mee, "and therefore would never again be the fighter he used to be." Worse, his quick loss in the second fight created suspicion of corruption.

In reality, Liston was still a formidable fighter and highly ranked contender at the end of his career, having won 15 of his last 16 bouts, 14 by knockout.[67]

BoxRec ranks Liston as among the 10 best heavyweights in the world in 15 different years (1954–1956 and 1958–1969), placing him at No.1 from 1958 to 1962 and the fourth greatest of all time.[68][69] Ring magazine ranked him as the tenth greatest heavyweight of all time, while boxing writer Herb Goldman ranked him second and Sports Illustrated placed him third.[70][71] Alfie Potts Harmer in The Sportster ranked him the sixth greatest boxer of all time, pound for pound.[72] In his book, The Gods of War, Springs Toledo argued that Liston, when at his peak in the late 1950s and early 1960s, could be favored to beat just about every heavyweight champion in the modern era with the possible exception of Muhammad Ali.[73] This view is shared by boxing writer Frank Lotierzo who ranks Liston as one of the top 5 heavyweights of all time and possibly the best.[74] Liston and Ali were both inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Ali, in his autobiography, stated that in his prime the only two boxers who would have caused him serious trouble were "Ezzard Charles and a young Sonny Liston".[75]

In popular culture

[edit]Calypsonian Lord Melody recorded a song entitled "Clay Vs Liston", which was released as a single in 1965. The song's lyrics deal with the first fight between the two. The song appeared on the 1994 CD compilation Precious Melodies.

Ali, a film by director Michael Mann, was released in 2001. Will Smith was nominated for an Academy Award and a Golden Globe for his portrayal of Ali. Former boxer Michael Bentt played Liston.

Robert Townsend directed a 2008 film about Liston entitled Phantom Punch. Ving Rhames starred as Liston, and Andrew Hinkson portrayed Ali.

A wax model of Liston appears in the front row of the iconic sleeve cover of The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. He is seen in the far left part of the row, wearing a white and gold robe, standing beside the original-look Beatles wax figures.[76]

As a homage to Sonny Liston, a bronze copy of a marble statue made by Alfred Hrdlicka in 1963/64 was put up in 2008 between Old Castle and Karlsplatz in downtown Stuttgart, Germany.[77]

In NCIS, director Leon Vance, a former boxer, has a framed photo in his office of Ali gloating over the floored Liston at the end of the second fight. In "Last Man Standing", he discusses the photo with Gibbs and mentions the fixing allegations.

A play entitled One Night in Miami opened in 2013. It tells the story of the night Ali—then Cassius Clay—beat Liston to take the World Heavyweight Championship. It takes place in a hotel room after the fight where Clay, Jim Brown, Sam Cooke and Malcolm X talk about their lives and their hopes for the future.[78] A film adaptation of the play was released in 2020.

The Mad Men episode "The Suitcase" from Season 4 revolves around the second fight, with Don Draper creating a commercial inspired by the famous photo.

References

[edit]- ^ "Sports Illustrated honors world's greatest athletes". CNN. December 4, 1998. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014.

- ^ a b "Quick look at facts, figures". Miami News. February 25, 1964. p. 2B.

- ^ a b c Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Thomas Hauser

- ^ quoted in Sonny Liston, Paul Gallender

- ^ a b c Sonny Liston, Paul Gallender

- ^ Irusta, Carlos (2012-01-17). "Dundee: Ali was, still is 'The Greatest'". ESPN. Retrieved 2012-01-17.

- ^ a b "King of the World". Penguin Random House Secondary Education. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Lipsyte, Robert (February 26, 1964). "Clay Wins Title in Seventh-Round Upset As Liston Is Halted by Shoulder Injury". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2008.

Poetry and youth and joy had triumphed over the 8-1 odds.

- ^ Dennis, Felix (2003). Muhammad Ali. Miramax Books. p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Gallender, op cit

- ^ a b c Harvey Jones and Jesse Bowdry appearance on CBS' I've Got a Secret, February 24, 1964. Rebroadcast on Game Show Network on March 24, 2008.

- ^ Kalb, Eliot (2007). The 25 Greatest Sports Conspiracy Theories of All-Time: Ranking Sports' Most Notorious Fixes, Cover-Ups and Scandals. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-089-8.

- ^ Paul Gallender, op cit

- ^ "Muslim Charge Clams Up Clay". The Pittsburgh Press. February 7, 1964.

- ^ a b Hauser, Muhammad Ali

- ^ "Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X – Rare 1965 Interview". Boxing Hall of Fame. July 4, 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b c Kirkby, Evans (February 25, 1964). "Howling Ali fined $2,500 for his antics at weigh-in". Milwaukee Journal. p. 11.

- ^ The Fight of the Century" Ali vs. Frazier, March 8, 1971, Michael Arkush

- ^ Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Thomas Hauser

- ^ Hoffer, Richard (29 November 1999). "A Lot More Than Lip Service". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ "Sonny Liston and Muhammad Ali Statistics Wood Print by Bettmann".

- ^ Hauser, op cit

- ^ a b c Tosches, Nick (2000). The Devil And Sonny Liston. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316897752

- ^ Muhammad Ali, Thomas Hauser

- ^ interview with Alex Haley in Muhammad Ali by Thomas Hauser,

- ^ Remnick, King of the World

- ^ a b Tosches, Nick (2000). The Devil And Sonny Liston. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316897752.

- ^ "1964 Clay vs. Liston Judges' Scorecards from Miami Beach Bout..." Sports.ha.com. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ Bob Mee, Ali and Liston

- ^ "Clay Admits Joining Black Muslim Sect". Lodi News-Sentinel. February 28, 1964.

- ^ Judge, E.J. "The Beatles & Cassius Clay Meet in the Ring". WCBSFM 101.1. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Luckhurst, Samuel (6 March 2014). "Cassius Clay Was Renamed Muhammad Ali 50 Years Ago Today". Huffinton Post. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Machen Backs Clay's 'Liniment' Complaint". Sarasota Journal. February 28, 1964.

- ^ "The Telegraph - Google News Archive Search". News.google.com. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ David Remnick, King of the World, pg. 202

- ^ Maule, Tex (March 9, 1964). "Yes, it was good and honest". Sports Illustrated: 20. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013.

- ^ Gallender, Sonny Liston, op cit

- ^ Ali, Muhammad; Goodman, Bob (February 1975). "Best I Faced: Muhammad Ali". The Ring. Retrieved December 12, 2023.

- ^ Daley, Arthur (February 27, 1964). "Another Surprise". The New York Times.

- ^ Gardner, David (February 25, 2014). "Clay's defeat of Liston 'was underworld fix'". London Evening Standard. p. 25.

- ^ Loverro, Thom (February 24, 2014). "FBI suspected iconic 1964 Ali-Liston fight was rigged by mob". The Washington Times.

- ^ Kantowski, Ron (February 26, 2014). "Fixed? Ali-Liston story mostly shadow, little substance". The Washington Times.

- ^ Kirkby, Evans (May 25, 1965). "Boasts and threats past, only the fighting remains". Milwaukee Journal. p. 14.

- ^ "Rev. King Gives Clay Advice". Lawrence Journal-World. March 20, 1964.

- ^ "Policeman Says Liston Was 'Unruly'". The News and Courier. March 12, 1964.

- ^ "Rematch Clause Clouds Clay's Contract". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. March 26, 1964.

- ^ quoted in Gallender, op cit

- ^ "Clay-Liston Fight Goes To Lewiston, ME". Gettysburg Times. May 8, 1965.

- ^ Allen, Mel. "The Night Lewiston, Maine, Can Never Forget". Yankee Magazine. Yankee Publishing. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ^ "Behind the Greatest Photo of Muhammad Ali Ever Taken". Time. 3 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2017.

- ^ "Did Anybody See It?". The Evening Independent. May 26, 1965.

- ^ "'Didn't Panic', Says Walcott". The News and Courier. May 27, 1965.

- ^ "Clay Eyes 'Rabbit' After Quick Win". Spokane Daily Chronicle. May 27, 1965.

- ^ HBO Documentary Sonny Liston: The Mysterious Life and Death of a Champion

- ^ "Little Larry Merchant". Boxing.com. Archived from the original on 29 July 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Nack, William. "O Unlucky Man: The sad life and tragic death of Sonny Liston". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ a b Merchant, Larry (6–13 July 2015). "The Phantom Punch". The New Yorker (letter). Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ "Sonny Liston vs. Amos Lincoln - BoxRec". Boxrec.com. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "25 Years Later: A Fix or a Fist?". Los Angeles Times. May 25, 1990.

- ^ Thomas Hauser (1991), Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0671688928

- ^ "A Quick, Hard Right And A Needless Storm Of Protest". Sports Illustrated. June 7, 1965. Archived from the original on March 14, 2014.

- ^ "Boxing by the Book: "The Real Story Behind the Ali-Liston Fights"". Boxing.com. September 19, 2012.

- ^ Shaun Assael (2017). The Murder of Sonny Liston: A Story of Fame, Heroin, Boxing & Las Vegas. Pan. ISBN 9781509814831

- ^ "Leyton Unsure About Future As Fighter". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. July 1, 1970. p. 20. Retrieved 24 November 2021 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ Andrew Vachss (2003), Only Child,[permanent dead link] p. 89, Vintage. Vachss further explains the way such a fix would have been engineered in Two Trains Running, pp.160–165, 233, Pantheon, 2005.

- ^ "Fifty Years Later: The Mystery of Muhammad Ali's 'Phantom Punch'". NDTV Sports. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Nick Tosches (2000). The Devil And Sonny Liston. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0316897752

- ^ "BoxRec's Annual Ratings: Heavyweight Annuals". BoxRec. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "BoxRec: Ratings". BoxRec. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "25 Greatest Fighters of All Time (Heavyweight)". M-baer.narod.ru. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "All-Time Greatest Heavyweights". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Top 25 Greatest Boxers of All Time". The Sportster. 19 August 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Book Review: 'The Gods of War' by Springs Toledo". Boxing.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Lotierzo, Frank (21 August 2012). "Lotierzo's Lowdown – Sonny Liston: The Most Underrated Heavyweight Champ In History". The Sweet Science. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Ali, Muhammad; Durham, Richard (1975). The Greatest: My Own Story. Random House.

- ^ Evans, Mike, ed. (1984). The Art of the Beatles,. United Kingdom: Anthony Blond (Muller, Blond & White). pp. 69–70. ISBN 0-85634-180-0.

- ^ Stuttgarter Amtsblatt No. 9, 1 March 2018, p. 8

- ^ "'One Night In Miami', More Than Clay Beats Liston". NPR.org. August 12, 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Hutchison, Phillip J. "From Bad Buck to White Hope: Journalism and Sonny Liston, 1958–1965." Journal of Sports Media 10.1 (2015): 119-137. online

- Olsen, Jack. Black is Best: The Riddle of Cassius Clay, (1967).

- Steen, Robert. Sonny Liston-His Life, Strife and the Phantom Punch (JR Books, 2008).

- Tosches, Nick. The Devil and Sonny Liston (2000) excerpt

External links

[edit]- Cassius Clay versus Sonny Liston. Theatre Network Television. ESPN Classic. February 25, 1964. Archived from the original on December 3, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2023 – via kumite27 (YouTube).

- Boxing matches involving Muhammad Ali

- World Boxing Council heavyweight championship matches

- 1964 in boxing

- 1965 in boxing

- Boxing in Florida

- Boxing in Maine

- Sports in Miami-Dade County, Florida

- Sports in Lewiston, Maine

- 1964 in sports in Florida

- 1965 in sports in Maine

- February 1964 sports events in the United States

- May 1965 sports events in the United States

- Boxing matches in the United States

- Boxing on ABC