Public lecture

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (February 2014) |

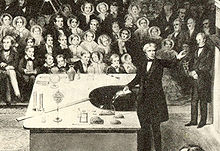

A public lecture (also known as an open lecture) is one means employed for educating the public. Gresham College, in London, has been providing free public lectures since its founding in 1597 through the will of Sir Thomas Gresham. The Royal Society held its first ever meeting at Gresham College in November 1660, after one of Christopher Wren's lectures, and continued to meet there for the next fifty years.[1]

The Royal Institution of Great Britain has a long history of public lectures and demonstrations given by prominent experts in the field. In the 19th century, the popularity of the public lectures given by Sir Humphry Davy at the Royal Institution was so great that the volume of carriage traffic in Albemarle Street caused it to become the first one-way street in London. The Royal Institution's Christmas Lectures for young people are nowadays also shown on television. Alexander von Humboldt delivered a series of public lectures at the University of Berlin in the winter of 1827–1828, that formed the basis for his later work Kosmos.

Public autopsies

[edit]Besides public lectures, public autopsies have been important in promoting knowledge of medicine. The autopsy of Dr. Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, advocate of phrenology, was conducted in public, and his brain, skull, and heart were removed, preserved in jars of alcohol, and put on display to the public. Public autopsies have verged on entertainment: American showman P. T. Barnum held a public autopsy of Joice Heth after her death. Heth was a woman whom Barnum had been featuring as being over 160 years old. Barnum charged 50 cents admission. The autopsy demonstrated that she was between 76 and 80 years old.

References

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Rhetoric |

|---|

|

- "Heritage". The Royal Institution of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 4 February 2005. Retrieved 26 January 2005.

- "Review of 'The Showman and the Slave: Race, Death, and Memory in Barnum's America' by Benjamin Reiss". Gary Cross, Journal of American History. Archived from the original on 28 December 2004. Retrieved 26 January 2005.

- "Mind Games: A look at phrenology in the 1830s". Tom Kelleher, Research Historian, Old Sturbridge Visitor, Fall, 1997; pp. 13–15. Archived from the original on 24 June 2001. Retrieved 26 January 2005.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- Online Lectures. Webcasts

- Lecturefinder: Search academic and college grade lectures online.

- platformed.org: A New York-based organization advocating public lecture attendance.

- yovisto.com: An academic e-lecture search engine.

- Open Lectures and Talks : Find lists of UK public lectures and talks

References

[edit]