Dipyridamole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Persantine, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682830 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 37–66%[1] |

| Protein binding | ~99% |

| Metabolism | Liver (glucuronidation)[2] |

| Elimination half-life | α phase: 40 min, β phase: 10 hours |

| Excretion | Biliary (95%), urine (negligible) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.340 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

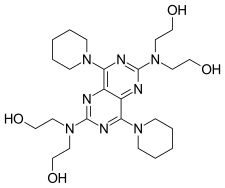

| Formula | C24H40N8O4 |

| Molar mass | 504.636 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Dipyridamole (trademarked as Persantine and others) is a nucleoside transport inhibitor and a PDE3 inhibitor medication that inhibits blood clot formation[3][dead link] when given chronically and causes blood vessel dilation when given at high doses over a short time.

Medical uses

[edit]- Dipyridamole is used to dilate blood vessels in people with peripheral arterial disease and coronary artery disease.[4]

- Dipyridamole has been shown to lower pulmonary hypertension without significant drop of systemic blood pressure.

- It inhibits formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (MCP-1, MMP-9) in vitro and results in reduction of hsCRP[clarification needed] in patients.

- It inhibits proliferation of smooth muscle cells in vivo and modestly increases unassisted patency of synthetic arteriovenous hemodialysis grafts.[5]

- It increases the release of tissue plasminogen activator from brain microvascular endothelial cells.

- It results in an increase of 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid and decrease of 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in the subendothelial matrix and reduced thrombogenicity of the subendothelial matrix.

- Pretreatment it reduced reperfusion injury in volunteers.

- It has been shown to increase myocardial perfusion and left ventricular function in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.

- It results in a reduction of the number of thrombin and PECAM-1 receptors on platelets in stroke patients.

- Cyclic adenosine monophosphate impairs platelet aggregation and also causes arteriolar smooth muscle relaxation. Chronic therapy did not show significant drop of systemic blood pressure.

- It inhibits the replication of mengovirus RNA.[6]

- It can be used for myocardial stress testing as an alternative to exercise-induced stress methods such as treadmills.

Stroke

[edit]A combination of dipyridamole and aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid/dipyridamole) is FDA-approved for the secondary prevention of stroke and has a bleeding risk equal to that of aspirin use alone.[4] Dipyridamole absorption is pH-dependent and concomitant treatment with gastric acid suppressors (such as a proton pump inhibitor) will inhibit the absorption of liquid and plain tablets.[7][8][9][10]

However, it is not licensed as monotherapy for stroke prophylaxis, although a Cochrane review suggested that dipyridamole may reduce the risk of further vascular events in patients presenting after cerebral ischemia.[11]

A triple therapy of aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole has been investigated, but this combination led to an increase in adverse bleeding events.[12]

- Vasodilation occurs in healthy arteries, whereas stenosed arteries remain narrowed. This creates a "steal" phenomenon where the coronary blood supply will increase to the dilated healthy vessels compared to the stenosed arteries which can then be detected by clinical symptoms of chest pain, electrocardiogram and echocardiography when it causes ischemia.

- Flow heterogeneity (a necessary precursor to ischemia) can be detected with gamma cameras and SPECT using nuclear imaging agents such as Thallium-201, Tc99m-Tetrofosmin and Tc99m-Sestamibi. However, relative differences in perfusion do not necessarily imply any absolute decrease in blood supply in the tissue supplied by a stenosed artery.

Other uses

[edit]Dipyridamole also has non-medicinal uses in a laboratory context, such as the inhibition of cardiovirus growth in cell culture. [citation needed]

Drug interactions

[edit]Due to its action as a phosphodiesterase inhibitor, dipyridamole is likely to potentiate the effects of adenosine. This occurs by blocking the nucleoside transporter (ENT1) through which adenosine enters erythrocyte and endothelial cells.[13]

According to Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2016 guidelines, dipyridamole is considered to not cause risk of bleeding when receiving neuroaxial anaesthesia and deep nerve blocks. It does not therefore require cessation prior to anaesthesia with these techniques, and can continue to be taken with nerve block catheters in place.[14]

Overdose

[edit]Dipyridamole overdose can be treated with aminophylline[2]: 6 or caffeine which reverses its dilating effect on the blood vessels. Symptomatic treatment is recommended, possibly including a vasopressor drug. Gastric lavage should be considered. Since dipyridamole is highly protein bound, dialysis is not likely to be of benefit.

Mechanisms of action

[edit]Dipyridamole has two known effects, acting via different mechanisms of action:

- Dipyridamole inhibits the phosphodiesterase enzymes that normally break down cAMP (increasing cellular cAMP levels and blocking the platelet aggregation, response[4] to ADP) and/or cGMP.

- Dipyridamole inhibits the cellular reuptake of adenosine into platelets, red blood cells, and endothelial cells, leading to increased extracellular concentrations of adenosine.

Experimental studies

[edit]Dipyridamole is currently undergoing repurposing for treatment of ocular surface disorders. These include pterygium and dry eye disease. The first report of topical dipyridamole's benefit in treating pterygium was published in 2014.[15] A subsequent report of outcomes in 25 patients using topical dipyridamole was presented in 2016.[16]

References

[edit]- ^ Nielsen-Kudsk F, Pedersen AK (May 1979). "Pharmacokinetics of dipyridamole". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 44 (5): 391–399. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1979.tb02350.x. PMID 474151.

- ^ a b "Aggrenox (aspirin/extended-release dipyridamole) Capsules. Full Prescribing Information" (PDF). Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "Dipyridamole" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ a b c Brown DG, Wilkerson EC, Love WE (March 2015). "A review of traditional and novel oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 72 (3): 524–534. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.10.027. PMID 25486915.

- ^ Dixon BS, Beck GJ, Vazquez MA, Greenberg A, Delmez JA, Allon M, et al. (May 2009). "Effect of dipyridamole plus aspirin on hemodialysis graft patency". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (21): 2191–2201. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0805840. PMC 3929400. PMID 19458364.

- ^ Dipyridamole in the laboratory: Fata-Hartley CL, Palmenberg AC (September 2005). "Dipyridamole reversibly inhibits mengovirus RNA replication". Journal of Virology. 79 (17): 11062–11070. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.17.11062-11070.2005. PMC 1193570. PMID 16103157.

- ^ Russell TL, Berardi RR, Barnett JL, O'Sullivan TL, Wagner JG, Dressman JB (January 1994). "pH-related changes in the absorption of dipyridamole in the elderly". Pharmaceutical Research. 11 (1): 136–43. doi:10.1023/a:1018918316253. hdl:2027.42/41435. PMID 7908130. S2CID 12877330.

- ^ Derendorf H, VanderMaelen CP, Brickl RS, MacGregor TR, Eisert W (July 2005). "Dipyridamole bioavailability in subjects with reduced gastric acidity". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 45 (7): 845–50. doi:10.1177/0091270005276738. PMID 15951475. S2CID 36579161.

- ^ "Persantin Retard 200mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". Electronic Medicines Compendium (EMC). Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- ^ Stockley I (2009). Stockley's Drug Interactions. The Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-424-3.

- ^ De Schryver EL, Algra A, van Gijn J (July 2007). Algra A (ed.). "Dipyridamole for preventing stroke and other vascular events in patients with vascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD001820. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001820.pub3. PMID 17636684.

- ^ Sprigg N, Gray LJ, England T, Willmot MR, Zhao L, Sare GM, Bath PM (August 2008). Berger JS (ed.). "A randomised controlled trial of triple antiplatelet therapy (aspirin, clopidogrel and dipyridamole) in the secondary prevention of stroke: safety, tolerability and feasibility". PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2852. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2852S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002852. PMC 2481397. PMID 18682741.

- ^ Gamboa A, Abraham R, Diedrich A, Shibao C, Paranjape SY, Farley G, Biaggioni I (October 2005). "Role of adenosine and nitric oxide on the mechanisms of action of dipyridamole". Stroke. 36 (10): 2170–5. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000179044.37760.9d. PMID 16141426. S2CID 1877425.

- ^ AAGBI Guidelines Neuraxial and Coagulation June 2016

- ^ Carlock BH, Bienstock CA, Rogosnitzky M (January 2014). "Pterygium: nonsurgical treatment using topical dipyridamole - a case report". Case Reports in Ophthalmology. 5 (1): 98–103. doi:10.1159/000362113. PMC 3995373. PMID 24761148.

- ^ Rogosnitzky M, Bienstock CA, Issakov Y, Frenkel A (March 2016). Topical Dipyridamole for Treatment of Pterygium and Associated Dry Eye Symptoms: Analysis of User-Reported Outcomes. ISVER (Israeli Society for Vision and Eye Research) affiliate of ARVO (Association of Research in Vision and Ophthalmology). Kfar Maccabia, Israel. Retrieved 19 May 2019 – via ResearchGate.